buildingondowntown, Mark Sterling

buildingondowntown, Mark Sterling

Introduction – Toronto, Open Source Metropolis (see fig.1)

The City of Toronto(1) today and downtown Toronto in particular, has evolved into something akin to an “open source” metropolis. As a result of the combination of a number of phenomena Toronto has become a city whose character and trajectory of growth is more difficult to ascertain than those of the more singular or iconic North American metropolises – New York and Chicago come to mind. It is free of the symbolic and mythical burdens and the attendant genius loci that characterizes those places and in some ways makes many of their potential lessons in urbanism difficult to emulate.

The openness to reinterpretation that the urban structure of Toronto has exhibited over time regularly renders paradoxical efforts to “plan” for change in that urban structure. In recent decades in Toronto, the ability of such plans to direct – and perhaps more importantly - to predict where and how change will occur has come into question.

This has led to a further questioning - of the usefulness of conventional planning activities and instruments. Citizens, who have become increasingly engaged in the debate about the future of their city, are frustrated that in-force planning documents have little or no authority in the face of development proposals.

The development industry tends to see both new and long standing planning permissions to be either outdated or out of touch with economic realities driving development. Even when there are relatively up to date planning instruments, they are seen by most participants in the planning process as the most likely starting point for even further amendments and applications for increases in scale and height of proposed new buildings.

Speculation on the scale of development that could potentially be approved on individual properties has led to inflation of their perceived value. Based on the preservation of those perceived values, and the lack of certainty in the outcomes of the planning process, there has been inflation in the scale of proposed buildings at the application stage. Developers, understanding that reductions in building size during the negotiation of development approvals are inevitable, sometimes propose “straw man” schemes that are larger than the desired development.

Development pressure in Toronto also stems from the shift of Provincial policy emphasis from suburban expansion to urban intensification as a result of the “Places to Grow” legislation and other related provincial policy statements. This shift was at its base an environmental sustainability strategy, understanding that more efficient use of scarce resources and a rational approach to the use of existing and future infrastructure resources would be served by intensification within defined growth boundaries.

As a result of the combination of factors discussed above, questions about the proliferation and scale of new very tall buildings in Toronto are at the forefront of a questioning of conventional approaches to planning and regulation.

This article takes as its focus the planning policy, development and construction of primarily residential mixed-use buildings as this is the sector within which the majority of the growth in the City of Toronto over the past four decades (1974 and earlier through 2013-14) has taken place.

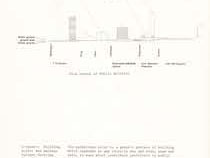

Planning and Regulation - A Retrospective Look Ahead (see fig. 3-5)

Since the beginning of the application of modern planning principles in Toronto in the early part of the twentieth century(2) there has been a tension between the simultaneous need to plan for the growth of the City and the need to regulate development on a day-to-day basis. In Toronto today (in 2013) this conventional tension is heightened by the fact that the operational development regulations were formulated for the most part in the early 1950’s when Metropolitan Toronto’s first consolidated city-wide Zoning By-law was created(3). Further tension has been added by the publication of a series of Official Plans that have gradually removed specificity and metrics related to development while at the same time, offering ever more aspirational plans and visions of the future growth of the City.

The 1950’s By-laws were for the most part a documentation of the physical form and land use pattern of the place, as it existed at that time. Over the ensuing decades these 1950’s regulations have been amended continuously in response to a mixture of proposals of additional height and density or land use changes for individual properties or assemblies of properties.

The process by which even the most progressive of these amendments to the regulations governing development in the city have been made (and the Official Plan where amendments were also made to it) has almost always been retrospective in nature where the actual zoning regulations are concerned. Amendments have almost always been made on a site specific basis – introducing the concern (or assumption) that individual amendments will have the inevitable effect of setting a “precedent” for the next amendment or proposal. This is yet another source of the tension that accompanies all debate about the future form of the city. It colours all attempts to reach the societal consensus about that future which coordinated Official Plans and By-laws are ideally meant to embody.

One unintended consequence of this retrospective approach to planning and regulation in the face of the rapidity of change on the ground has been the emergence of an openness about the future form of the City. This openness is perceived by some as offering exhilarating possibilities and by others as a failure of society to be able to plan at all.

“onbuildingdowntown” – Toronto, City of Towers (1)

The title of this article “buildingondowntown” is a reformulation of the title of the seminal treatise on the built form and public realm of the central core of the City of Toronto – “onbuildingdowntown” and the companion study “Built-Form Analysis” both of which were co-authored by George Baird, Steven McLaughlin and Roger duToit et al and published in 1974 by the City of Toronto. (see figs. 6-8)

These two documents were written in response to new provincial development control legislation to inform the development of a new Central Area Plan and associated Zoning By-laws. This new Plan and By-laws were to include new approaches to built form based and planning and a scientifically based approach to the discussion of the urban environment – an important alternative approach to understanding, planning and to the regulation of the intensification of the historical central core of the City.

These documents spawned several generations of subsequent planning and urban design policy documents. Together they have gradually built up a culture of planning and a family of zoning regulations the primary goals of which are achieving: higher degrees of “predictability” of built form outcomes; more consistency and higher quality in the public realm and in the publicly accessible elements of the private realm. Although there was guidance provided for the public sector and its projects, the primary focus of these documents was guidance for the activities of private development industry that builds the majority of the city.

In “onbuildingdowntown” the authors note in their introduction that:

“In recent times a great deal of public concern has been expressed by the people of Toronto about the nature and extent of change in the City’s Core Area. This ranges from concern about the concentration of particular types of development, particularly in relation to the available transportation capacities and problems, to concern about the adverse effects the design of particular developments can have on the public environments such as the streets.”(4)

In Section 2 Philosophy the authors opine on the shortcomings of zoning:

“The present system of zoning is not adequate. … It is a concept related to definable, isolated parcels of land, not to the more important issue – the relatedness of these parcels – their connections and their impacts on neighbouring lands. The current set of rigid controls forces the participants in the development process into a reactive position. … We also appreciate the inability of zoning to address itself to connections and impact. The need for re-appraisal is evident.”(5)

In proposing an instrumental role for the “design guideline” as a result of their study they also recognize the inherent limits of the guideline as a tool stating that:

“The purpose of the guidelines approach is to enable the creative attainment of public objectives for private development and to free the designers of individual projects from a straight jacket of specific regulations, which are all too often inappropriate to a particular development situation. Design guidelines cannot be accepted as a cure-all for the deficiencies of planning or zoning.”(6)

The form of buildings anticipated and informed by “onbuildingdowntown” and “Built Form Analysis” were to satisfy the stated primary goals of:

- Expansion and elaboration of the public realm in the Core Area;

- Increasing the range and quality of publicly accessible spaces in the private realm;

- Encouragement of a more considered and more imaginative approach to the enhancement of the Core Area;

- Encouragement of pattern of public views of interesting activities from both the public realm and the publicly accessible parts of the private realm;

- Increasing the accessibility of Core Area facilities;

- Increasing the use in design of the natural phenomena of everyday life; and

- The integration of the above in a “characteristic Toronto urban form”.

The recommendations for future built form contained in “onbuildingdowntown” and “Built Form Analysis” were directed primarily toward incremental infill redevelopment opportunities within the existing urban fabric of the downtown areas of Toronto.

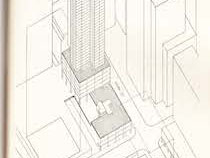

The approach taken was first and foremost a response to context – in search of a new but “characteristic Toronto urban form”. When dealing with tall building situations “onbuildingdowntown” and “Built Form Analysis” in particular recommended the creation of a base building form that managed the “fit” between the existing context and the new development, and created more or less conventional interfaces and framing relationships between the building and the public realm.

The tall building elements located, as recommended, above the base or podium would be positioned to create favorable wind conditions and access to sunlight on the nearby public realm in order to encourage pedestrian activity on the city streets in appropriate environmental conditions. “Built Form Analysis” included a large number of case studies or individual site test fits of this relatively new form of “well-tempered” tall building on downtown Toronto sites.

This use of the “podium tower” typology in the design of tall buildings has become the norm in Toronto over the years. The typology has found its way into subsequent design guidelines and zoning by-laws and is often contrasted with the previously favoured approach to tall building design, that being the use of a so called “tower in the park” typology.

Of course, building technology and the pace of growth in Toronto being what they were in the 1970’s, the scale of the tall building elements that were modeled and tested using this podium tower typology, were at heights of 20-25 storeys (60-76m) at their highest. Buildings of this type and scale were only anticipated in the most concentrated downtown areas of the city – in its downtown area.

300 Cranes – Toronto, a City of Towers (2) (see fig. 9)

A new scale and pattern of urbanism has emerged and continues to emerge in Toronto. This isan urbanism that can be characterized as a patchwork archipelago of clusters of very dense and very tall urban artifacts in the “sea” of the City’s more “conventional” urban fabric.(7) What is emerging in many ways challenges the concept of the well-tempered, context-driven tall buildings that were to have extended what was then understood to be the “characteristic Toronto urban form” that was generally anticipated by “onbuildingdowntown” and “Built Form Analysis”.

Emerging sometimes in relatively predictable locations in the intensification areas designated as “Downtown” or “Centres” in Toronto’s Official Plan - and more recently in rather unexpected locations as a result of patterns of land ownership and assembly - this new form of urbanism is often driven by what seems at the outset to be singular development “opportunities” at an unprecedented scale.

These “opportunities” in fact turn out to be harbingers of a new wave of development pressure in an area that will eventually exhibit a dramatically different scale from that of the preceding periods of development – and from that which is anticipated by the “official” planning for those areas.

Visitors to Toronto and residents (and local developers, design and planning professionals and academics if the truth is to be told) are constantly struck by the number of construction cranes in and around the downtown, the waterfront and designated mid-town centres and the transit corridors of the city. Estimates put the number of construction cranes currently on sites in Toronto at between 200 and 300 depending on the boundaries for the count.

Despite recent global economic challenges, the City of Toronto has continued to grow through primarily private development in a relatively uninterrupted fashion – with fits and starts but without the shut downs and recession-related shrinking of the development and construction industry that has been the case in other countries around the world. The continued success of Toronto as a location for development is in many ways driven by those “dire straits” experienced elsewhere. Foreign investment in the relatively safe haven of the Canadian economy and Canada’s relatively open immigration policy are key parts of the engine driving development and investment in real estate in Toronto (and the rest of Canada to a greater or lesser extent).

The condominium industry is a particular focus of international investment in development in Toronto. It is estimated by some that as much as 20-30% of the purchases of condominium units in the GTA (Greater Toronto Area) are made by “investors” who will not live in the units but will rent them to third parties. This has resulted in the city’s condominium buildings becoming the primary new source of rental accommodation.

Current facts about Downtown Toronto:

- Approximately 25 buildings taller than 100m are under construction and scheduled for completion in the next three years, most of which are in downtown Toronto.

- Toronto is currently ranked as third in North America and seventh in the world among cities with the greatest number of tall buildings, using the threshold of 100m.

- It is estimated that there are approximately 160 existing tall buildings in Toronto and that close to 120 more are in the approvals process or under construction as of the date of this article.

- The Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (CTBUH), which recently opened its Toronto chapter, describes Toronto as the most active city for tall buildings in the Western hemisphere. Data also indicate that 23 of the 25 tallest buildings to be completed in Toronto by 2016 are being built for residential use and that five will be taller than 200 metres.

- Aura at College Park, scheduled for completion in 2014, will be the fourth tallest building in Toronto at 272 metres. When complete Aura will be the tallest residential mixed-use building in North America.

What is driving growth at this pace in Toronto?

- Toronto is currently the fourth largest city in North America, behind Mexico City, Los Angeles and New York.

- Critical Mass: Toronto has a population of 2.79 million people in the core of the larger Greater Toronto Area whose population is 5.5 million people; (8)

- Immigration: The Greater Toronto Area (GTA) is projected to be the fastest growing region of the province, with its population increasing by 2.5 million, or 39.1 per cent, to reach over 8.9 million by 2036.

- The GTA’s share of provincial population is projected to rise from 47.6 per cent in 2012 to 51.5 per cent in 2036;(9)

- Between 2001 and 2011, The City of Toronto's population grew by 133,500 persons, or 5%;

- Downtown Toronto has grown at an even quicker rate, with 41,800 new persons since 2011, growing by 27%;(10)

- By 2031, the Province anticipates that an additional 575,000 persons will be living in Toronto, increasing the city’s population by another 22%2(11); a large proportion of which will be located in the downtown;

- Employment in the City of Toronto is expected to grow by 342,000 jobs, or 25%, by 2031based on Provincial projections(12);

- Employment in downtown Toronto has grown dramatically over the last five years, up by 46,800 jobs, or 12%. Twenty additional new commercial office projects (975,000m2/10.5 millionft2) are proposed for Downtown. This additional commercial development represents approximately 52,000 new jobs in downtown Toronto.

- Foreign Investment in Canadian real estate as an international economic safe haven;

- Reinvestment in the Centre. Commercial office building boom in downtown core and south downtown reflects a reconsideration of the suburban exodus of the previous decades;

- Character and Amenity of the existing city in comparison to what is available in Toronto’s suburban areas;

- Demographic and Generational Shifts. As an example the decline in automobile use and ownership in the generation known as the “Millennials”;

- Slowing but stable long-term housing demand in the high-rise, or at least high-density forms, coupled with the decline in available low-rise (more suburban) forms;

- Absorption historically in the larger City of Toronto at 11,000 new dwelling unit sales per year (down in 2012 from a high of 20,000 in 2011);

- Ongoing demand is predicted for 4,000 to 5,000 units annually in downtown Toronto, based on past growth trends and improving character of the local area. Growth in the purpose built rental market is also forecasted.

1974/2002 – Reform/Re: Form

In the period between the publication of “onbuildingdowntown” in 1974 and 2002 the tallest buildings proposed in the City of Toronto were challenging, and in some cases going beyond the tallest of the downtown height limits - 76.0m heights (roughly 24 storeys).

The seventies, eighties and most of the 90’s in the City of Toronto saw steady growth, intermittently disrupted by a series of economic and construction downturns.

In general, developments during this period of growth were consistent with the built form focused city building principles and planning approaches established by “onbuildingdowntown” and “Built-Form Analysis”. This consistency was in part due to the translation of those approaches into City of Toronto planning and urban design policy, guidelines and practice. However, it was also due to the presence within the Toronto architectural, academic and development communities and within the City bureaucracy of key individuals who received their education, and in many cases their early professional training, from the authors and team members.

The so-called “reform” councils of the 1970’s initiated a period of city building using low and midrise development forms proposed by “onbuildingdowntown”. During this period, in Toronto important large-scale, generally mid-rise developments such as the St. Lawrence neighbourhood were the focus of progressive design and planning debates. At the same time there were a number of significant tall buildings developed in the city. The tallest residential building of that period, the Manulife Centre on Bloor and Charles Streets West (166m/51 storeys) (see fig. 10), was seen until very recently as an “anomaly” - a term that figures prominently in many City of Toronto planning reports attempting to come to grips with the role of tall buildings in the City.

The 1980’s saw the first of several condominium “booms”, characterized by buildings with large floor plates and relatively slab-like presences. Projects during this period tended to achieve maximum heights of approximately 35 storeys (100–110m) (see figs. 11, 12).

The 1990’s in Toronto saw a gradual increase in the heights and densities of proposed residential mixed-use buildings and corresponding attempts to rein in the proliferation of tall buildings and to create a more consistent approach to the creation of a high quality public realm through redevelopment by means of a suite of design guidelines. These came in two different forms: as city wide issue-based guidelines that were free-standing studies; and as district specific guidelines, generally developed through the secondary plan process.

Even when the built form and urban design principles of “onbuildingdowntown” were followed, the buildings proposed were often at heights that were higher than anticipated by the applicable zoning bylaws. This points to a persistent feature in the discussion about the history and future of city building in Toronto – that there is, a fundamental discrepancy between: the increasingly aspirational Official Plans; the collection of associated non-statutory “Design Guidelines” which are becoming more and more prescriptive; and the in-force general zoning by-laws – most of which are decades out of date and do not reflect current development realities.

This mismatch was further exacerbated in 1998 when the City of Toronto was amalgamated with surrounding, more suburban municipalities.

Recent attempts to consolidate the zoning bylaws of the former municipalities have further highlighted the mismatch. (It is important to note that in the pre-amalgamation period, the primary mismatch existed in the “former” City of Toronto. The surrounding municipalities in general had Official Plans and Zoning By-laws that were coordinated documents that reflected both the existing built fabric and the desired future development form.)

A critical influence on the shaping of the city during this period – and historically – has been the existence of the Ontario Municipal Board (OMB). The OMB is a quasi-judicial tribunal that hears applications and appeals in relation to a range of municipal planning, financial and other land development matters and other issues assigned to the Board by numerous Province of Ontario statutes including the Planning Act. Originally formed in the late 19th century as the Ontario Railway and Municipal Board (ORMB), the OMB eventually evolved into a body that administers provincial regulations of municipal matters.

In disposing of appeals of decisions of City of Toronto Council, the OMB has the authority to make any decisions that City Council is authorized to make on approvals. The vast majority of the recent wave of tall building proposals in Toronto has been adjudicated before the OMB.

In the Canadian context the existence of such an appeal process is unique. The OMB has played a critical role in the determination of the form of Ontario cities and Toronto in particular. It has been the venue for the consideration of individual development proposals in the face of the planning gap that continues to exist in Toronto between Official Plans and the more detailed but mostly outdated content of the Zoning Bylaw.

The existence of this appeal body is another source of tension in the debates about the future of the City. Many citizens and local politicians would prefer to see the OMB abolished in favour of more local control over planning and zoning matters. The development industry see the OMB as a “brake” on what is perceived to be a potentially over politicized planning process. (13)

For a number of reasons, successive generations of planners and politicians in the City of Toronto have found it impossible to approach the recalibration of the existing zoning by-law in order to guide the scale and configuration of future city growth.

A prime example of this is the arguably failed attempt to develop a new city-wide “main streets by-law” in the early 1990’s to direct intensification to Toronto’s transit corridors. The goal of this proposed change to the Zoning By-law was the implementation of a number of findings from an international competition(14) organized by the City of Toronto that examined the potential of those corridors to intensify through: the adoption of new typologies; the increase of residential densities; and optimize the utilization of exiting subway and streetcar infrastructure. Jane Jacobs was one of the jurors on this international competition.

Ironically, given Ms. Jacobs’ support of the intensification potential that the competition identified, the changes to the Zoning By-law foundered on the rocks of the broad public consultation process that was part of the implementation process (and has become an increasingly powerful factor in Toronto over the ensuing decades) and the consistently shallow depths of the typical “Main Street” properties.

Having found the development of detailed city-wide built form regulations to be difficult or even impossible to achieve, efforts to represent a consensus on the future form of the City were focused on the clarification of the former City’s Official Plan - which in the late 1980s was considered to be more of a technical document and contained detail which often conflicted with the Zoning By-law.

In the early 1990’s the process to create a new Official Plan (City Plan 1991) was supported by a number of quite detailed background documents(15) – many of which were ground breaking attempts to provide the basis for official implementation of approaches to built form, typology and the understanding of the morphology of the existing city first set out in “onbuildingdowntown”. Planners who commissioned these background reports and many of the authors were the same key individuals who received their education and, in many cases, their early professional training from Baird et al, the authors of “onbuildingdowntown”.

These comprehensive planning and urban design efforts (as well as a number of progressive policy and service delivery changes) were interrupted by the amalgamation of the City of Toronto with the surrounding municipalities in 1998. This amalgamation was enforced by provincial legislation under the Conservative government of Premier Mike Harris, despite a referendum that indicated that a majority of the residents of Toronto and the surrounding municipalities did not want to amalgamate.

The new ”Megacity”, as it was referred to at the beginning of its existence, was characterized by a dense central core supported by a relatively robust transit system. (see fig. 13) This was surrounded by a set of uniquely Canadian suburban territories that included multiple distributed pockets of intensity surrounded by seas of single-family houses.

The process of the creation of the New Official Plan for the amalgamated “Megacity”, , extended a number of the progressive, built form-based guidelines of the 1991 Official Plan for the central city, while attempting to recognize the differences in form, density and aspiration between the centre and periphery. The technical aspects of the 1991 Plan were mostly eliminated in favour of more “high level” policies that focused on “three lenses” through which the future of the City would be seen. These were:

- the residential neighbourhoods, which were expected to see little physical change;

- areas that were “ripe for major growth” such as the Centres, the Port Lands and large vacant sites, with unique situations that require local plans; and

- areas of change which are parts of the city where there are opportunities for a more gradual process of incremental change such as the city’s main shopping streets and certain institutional lands.

The new Official Plan of the “Megacity” was adopted by City Council in 2002.

“For What Its Worth”- An Uneasy Consensus 2002 – 2013

Subsequent to Council’s approval of the new Official Plan in 2002, City Planning undertook to amalgamate the Zoning By-laws that were still in force. These were the original By-laws of each of the former municipalities that were formed after the Second World War (Etobicoke being the first in 1949). Over the intervening years all 43 of the pre-existing individual By-law documents were repeatedly and, in some cases, massively amended. This amalgamation of the pre-existing by-laws proved to be a daunting and ultimately impossible task.

The result of several years of work, Toronto now has a new comprehensive zoning bylaw, whose primary feature is a new common nomenclature. The specific content of the preexisting By-laws continues to operate virtually unchanged. It appears from this result, that the Zoning By-laws (like some other aspects of the governance and management of the “Megacity”) were too big to fix.

At the same time City Planning commenced the preparation of a number of City-wide Design Guidelines in order to provide more detailed guidance about the implementation the of the Official Plan than could be captured by the more “high-level” policies that it contained and to provide an ability to respond to changing circumstances and priorities over time.(17)

The years between 2002 and 2006 represent the threshold point for the development of very tall buildings in Toronto. During this period the Toronto saw:

- the final approval of the City’s most recent Official Plan by the OMB. (originally approved by City Council in 2002, it took an additional 4 years for the resolution of the majority of appeals to be resolved); and

- the approval of the first of a new generation of very tall mixed use buildings with the primary use being residential condominium units (over 50 storeys or approximately 155m), outside of the City’s Central Financial Core (which historically had no maximum height limits).

In many cases the first round of buildings that challenged contemporary height thresholds were part of large consolidated land holdings controlled by corporate development entities operating at arms-length from national transportation companies or upper level government landowners.

However, unlike the more recent but related phenomenon of the construction of ever-increasingly tall and dense buildings within and above the fabric of the existing city, these sites are really more like “internal peripheries”. Similar to “new towns” or so called “green, brown or grey field developments”, they can only be developed through the simultaneous construction of the new infrastructure that is necessary to support development where none exists or that which does exist is obsolete. The West Don Lands neighbourhood is one such district. (see fig. 14)

Strategies for the orderly development of these areas are typically set out in approved Secondary Plans. These include a cascading series of ever more detailed Precinct Plans, Zoning By-laws, Subdivision Agreements and Holding By-laws – followed eventually by Site Plan Approvals and Construction Permits for individual buildings. At each stage the municipality exercises its approval authority under the provincial Planning Act and Building Code to review plans for compliance within the approved documents and has the ability (as does the land owners or developer) to engage in Official Plan or Zoning Bylaw amendment or Minor Variance processes to effect major and/or minor changes to the approved plans.

Despite the fact that they are subject to Secondary Plans, in the ultimate build-out of these and other consolidated public or quasi-public lands, the heights of tower components have gradually crept higher. These large, comprehensively planned neighbourhoods all had highly detailed public realm plans that included the design of all associated streets, parks and private open spaces (and secure funding of the construction) and have created a dynamic presence in the skyline of the city.

Following more or less directly from the gradual upward pressure in height and density seen in the comprehensively planned lands, a series of new very tall buildings were proposed as infill development on individual properties or relatively small assemblies of properties in areas of the city that were nearby, but often outside of areas that were officially considered to be intensification areas.

The first of these buildings, at 2195 Yonge Street and known as “Minto Midtown”, is a 2-tower, 118m/160m, 37/51 complex by the developer Minto. (see fig. 15) It was designed by SOM and Zeidler Partnership Architects and was approved by the Ontario Municipal Board in 2002, after having been refused by City Council. This highly controversial development captured the attention of residents, politicians and bureaucrats, planners, architects and developers – to the extent that the approval had an effect on the municipal elections of the following year. The councilor at the time of the approval of Minto Midtown was perceived to have “lost the battle” to rein in the scale of development and was not re-elected.

Roughly contemporary to Minto Midtown is a series of initial proposals for tall buildings in a more downtown location by the developer Candarel Stoneridge and Toronto architects Graziani and Corrazza. Here there was a proposal for a series of ever taller towers in the completion of a large full block development called “College Park”.

Three new towers were proposed, all pushing well beyond the 76.0m heights (roughly 24 storeys) approved for the area in general and for the College Park block in particular. The first two were a pair of towers on a 3-storey base known as “The Residence of College Park”. These were 52 and 45 storeys, and were completed in 2006 and 2008 respectively.

With one remaining parcel in the key corner location at the intersection of Yonge and Gerrard Streets and approximately 93,000m2 of unused development potential, the developers secured permission to construct a 78 storey (273m) mixed-use building called “Aura at College Park” with 987 dwelling units and 17,000m2 of retail and commercial uses in its podium. Construction is nearing completion at the time of this writing. (see fig. 16)

As the first of the primarily residential proposals to surpass 200m in height, the Aura proposal again captured the attention of those concerned with the scale and pace of development in the City. It precipitated the convention of a project-specific “Design Review Panel” made up of noted architects and urbanists to assist the City planners, local Councilor, the proponents and the general public in understanding the implications of such an unprecedented tall building at College Park and on Yonge Street in particular. The Design Review Panel ultimately made recommendations for adjustments to the built form of the proposal but supported the unprecedented height of the building as a landmark element in the City’s skyline north of the financial core.

Although the focus of the debate in the planning of these buildings might appear from the foregoing to have been on the determination of the absolute height and density (and as a corollary, the economic return on investment to the proponents) but, in fact, much of the specific design consideration in these projects was about the way they meet the ground and support the creation of a high-quality public realm.

As part of its package of privately funded public amenities the Minto Midtown project included, a very successful public plaza space. This was set back from Yonge Street between the two towers complete with public art. While the Aura project did not create any new public open space, it did contribute funds to upgrade the existing Barbara Ann Scott Park in the centre of the College Park block and delivered an upgraded public sidewalk and landscaping of a closed section of public street to the north of the development.

The planning and approvals process for these two tall building developments was taking place during the period following the approval of the first new Official Plan for the amalgamated City.

While there is a legislated requirement for the Zoning By-laws and other planning instruments to be in conformity with the new Official Plan, in practice it has proven to be impossible for the City to create that comprehensive by-law.

Into the gap created by the absence of a truly new Zoning By-law, a series of issue-specific, generally city-wide urban design guidelines have been inserted. The creation of these guidelines was, in part, a response to the difficulty of responding to development proposals for tall buildings on sites where no previous Official Plan or Zoning By-law had ever anticipated them (such as the two instances described above).

During this period the discussion about development and its built form focused on the identification and mitigation of the “impacts” of development that are unacceptable, or to use the more commonly used descriptor, “undue”. The consideration of these impacts is primarily in relation to the public and private realms in the context area of a particular development.

The range of development impacts that are considered includes relatively quantifiable (or at least measurable) phenomena such as:

- increases in shadow on nearby open spaces and buildings, increases in wind speed in areas around proposed buildings where pedestrian activity is anticipated - including roof top and other private amenity spaces as well as the public sidewalks parks and open spaces;

- the incremental increase of vehicular traffic on the streets in the area and of course any pressure on the capacity of the existing sewer, water, electrical or other infrastructure.

Less “tangible” impacts of new development (and tall buildings in particular) that are frequently considered include:

- the diminution of “sky views” from the public realm;

- “visual impact” in general – considered to be overwhelming presences as a result of the high degree of visibility of tall buildings either as individual occurrences or as clusters; and

- the transition in scale that is effected between proposed development and adjacent generally lower scale development in the area.

The consideration of all of these impacts is informed generally by the Built Form policies of the City’s Official Plan and elaborated upon by the Design Guideline documents. This consideration takes place in the context of a robust and well-established pre and post development application public consultation processes.

Although the City has created a number of types of Guidelines those most relevant to the guidance of intensification and redevelopment opportunities are:

- “Design Criteria for the Review of Tall Building Proposals” (A consultant study prepared by HOK Architects (Toronto) on city-wide tall building guidelines adopted by City Council in 2006.) These guidelines underwent a period of testing, stakeholder consultation and revision and have, until very recently, been the point of reference for tall building approvals across the City. They were adopted in a revised final form by City Council in May 2013. (See below);

- “Tall Buildings: Inviting Change in Downtown Toronto” (A consultant study recommending locations and regulations for tall buildings within the officially designated “Downtown” area. It was submitted to the City of Toronto in April 2010 and prepared by Hariri Pontarini Architects and Urban Strategies Inc.). This study was the first attempt to predict or direct tall buildings to specific locations in the downtown. The locus of this form of development was to be the primary and secondary “High Streets” of the downtown with specific typological distinctions. Like the 2006 document it focused on the design of the “well mannered tower” and discussed a variety of approaches to mitigating “impacts” of tall buildings on their surroundings, such as increases in shadows and wind effects on adjacent properties and the public realm and the diminution of views of the sky from the public realm.;

- "Downtown Tall Buildings Vision and Performance Standards Design Guideline" (A guideline prepared by City Planning that built upon the 2010 document and subsequent additional public and industry consultation. It was adopted by City Council in July of 2012.) Adjustments were made to some of the areas where tall buildings were directed and to some of the terminology – particularly the replacement of “regulations” for tall building design” with “performance standards” as reflection of the non-statutory nature of the guidelines themselves;

- “Tall Building Design Guidelines” (a city-wide Tall Building Design Guidelines outside the Downtown was adopted by Council in May 2013.) These city-wide guidelines integrated and consolidated the performance standards and terminology developed in the 2012 Downtown Tall Buildings Vision and Performance Standards with the city-wide considerations and application of the 2006 document (what is this?). They do not identify specific areas outside of Downtown where tall building development is directed;

- “Downtown Tall Buildings: Vision and Supplementary Design Guidelines” (an appendix to the “city-wide “Tall Building Design Guidelines” that reprises the vision statements, mapping and seven Supplementary Design Guidelines relating either to the base conditions or the tower portion of tall buildings or to their contextual fit.

For details and links to the documents referred to above go to:

http://www.toronto.ca/planning/tallbuildingstudy.htm

Another related guideline that was prepared for the City is the:

- “Avenues and Mid-Rise Buildings Study” (A consultant study with Brook McIlroy Planning + Urban Design/Pace Architects adopted by City Council in 2010) The study which included vision statements and performance standards that were structured in a similar way to and clearly informed those in the most recent “Tall Buildings Design Guidelines” is intended to:

- evaluate the Official Plan “Avenues” designation (transit corridors identified for intensification similar to the earlier “Main Streets” program;

- identify best practices for new mid-rise buildings, and identify areas where the performance standards should be applied.

This study is relevant to the tall building discussion in that it is the assumed default or preferred form of intensification outside of those areas where tall buildings are directed or anticipated in the other guidelines.

For details and links to the Avenues and Mid-Rise Buildings Study referred to above go to:

http://www.toronto.ca/planning/midrisestudy.htm

In addition to the development of this suite of guidelines the City of Toronto Design Review Panel was approved by City Council as a pilot project in June 2006 and made permanent in November 2009. The Design Review Panel is a volunteer, advisory panel, whose members include Architects, Landscape Architects, Planners, Engineers and Heritage professionals. Members provide City staff with professional design advice on public and private development. Panel sessions are open to the public. Over the course of its existence it has been considered to have been successful in elevating the level of discussion of design in the planning process.

Quickly following the process that resulted in the 78 storey Aura project, several other significant tall buildings were approved by City Council in mid- downtown locations. Included among these are:

- Four Seasons Hotel and Condominium at 1263 Bay Street - 46 and 30 storey (179m and 110m) towers approved in 2006 ;

- 1 Bloor Street East in the Bloor Yorkville District - 78 storey (290.5m) approved in 2008 (see fig. 17);

- 50 St. Joseph Street, a multi tower project with its tallest elements significantly set back from Yonge Street - 55 and 45 storey (185m and 155m) towers approved in 2008 .; and

- 2 Bloor Street West (also known as Cumberland Terrace) a multi tower project at 48 and 36 storeys (162m and 125m) approved by OMB in 2010.

Other recent tall building activity further south in downtown during this period includes:

- The Shangri-La (James Cheng) 65 storeys (214.0m) completed in 2012;

- The Ritz Carlton (Kohn Pedersen Fox and Page + Steele / IBI Group Architects 53 storeys (210.0m) completed in 2012;

- The Trump Hotel and Tower (Zeidler Roberts) 65 storeys (277.0m) completed in 2012;

- The “L” Tower (Studio Daniel Libeskind and Page + Steele / IBI Group Architects) 57 Storeys (195m); (construction nearing completion) (see fig. 18)

- 50 Bloor Street West (Pellow + Associates Architects) 83 Storeys (277.0m). (in planning stages) (see fig. 19); and

- Mirvish Gehry Towers (Gehry and Partners) 82, 86 and 84 storeys (279.0m, 290.0m, 286.0m). (in planning stages, appealed to the OMB) (see fig. 20)

There are significant new and proposed tall buildings (including several new tall commercial office buildings) in the area south of the main downtown area. This is generally south of the rail corridor and Gardiner Expressway that both cut across the base of the City’s financial core, separating it literally and figuratively from the Lake Ontario waterfront. Some of these buildings have been constructed. Others are under construction, are approved or proposed. These include:

- 1 York Street / 90 Harbour Street (&Co Architects and Architects Alliance) a 186,000 m2 office/retail/residential complex with 37 storeys of office (174.0m) and two residential towers at 66 and 62 storeys (236.0m and 224.0mm), all set on a multi-level retail and amenity podium (see fig. 21);

- 10 York Street (Wallman Architects) 62 storeys (224.0m);

- Ice Condominium at York Centre (Architects Alliance) 57 and 67 storeys (174.0m and 204.0m);

- Maple Leaf Square (KPMB) 54 and 50 storeys (186.0m and 174.0m).

Also in the planning stages and further out in time is the development of several large former industrial sites immediately to the east of the cluster of projects described above. These include 1 Yonge Street, (see fig. 22) a large site that may have as many as five new very tall buildings clustered around a refurbished 1970’s office tower. The tallest of the proposed new residential buildings has been proposed at over 88 storeys (270.0m).

In the unbuilt areas of this part of downtown Toronto, to the east, urban design graduate students from the University of Toronto’s Program in Planning working with the author have suggested that there is the potential for up to 16 additional tall buildings – pending the outcome of negotiations between the City and the owners of these large parcels. Others who are directly involved in the planning of these areas have recently suggested that a higher number might actually be possible.

The projects referred to above do not comprise an exhaustive catalogue of all of the projects that have been proposed, approved or built in the City during this period of unprecedented growth. And, it is highly possible that another 20 development applications for very tall buildings could be submitted to the City, for properties in the downtown, within the next few years.

The “uneasy consensus” is a sense on the part of both participants in the planning and development process and the nearby residents and citizens of the City in general, that a process is underway that is not under the control of commonly understood regulatory systems. Instead there is a rather organic and dynamic process of pressure and resistance underway. Any equilibrium that is achieved between development proposals and mechanisms available to planning authorities or assumptions on the part of the general public is perceived by everyone involved and to observers to be unstable and transitory.

This is not to say that the results of this essentially “unregulated” growth have been negative for the city. On the contrary, this dynamic and admittedly unpredictable process has been able to create the equivalent of several medium-sized Ontario towns in terms of new residential population in the centre of the City. In a form of symbiotic response, the downtown - and particularly the south downtown - is now seeing significant growth in terms of employment opportunities as new office building development projects proceed.

The growth and concentration in the core of the existing city represents a significant step forward in the attempt to slow and eliminate urban sprawl in the Greater Toronto Area in fulfillment of the goals and objectives of the Province’s Growth Plan, the Metrolinx Big Move Plan and other intensification policies. Whether the existing and generally aging infrastructure of the City can support this intensification within the core is an open question that is being asked more and more often in the debates about both individual projects and larger city-wide planning issues.

The issue here is that, as the song says “…There's something happening here. But what it is ain't exactly clear”.(17)

buildingondowntown

The escalating scale of tall building development and the parallel development of an inability to respond with effective policy can, in the author’s opinion, be traced to a combination of events and responses to those events – set in motion by the forced amalgamation of the former City of Toronto with its surrounding more suburban municipal neighbours and the elimination of the regional government entity (Metropolitan Toronto) that had linked them together in the previous 35 years.

Despite attempts to export a built form-based planning regime to the larger amalgamated City, the post-amalgamation City of Toronto still lacks a truly coordinated set of planning instruments (Official Plans, Secondary Plans and Zoning By-laws). Such a coordinated suite of planning instruments, were it possible to create them, would set out a realistic vision of the future growth of the City and follow it up with more detailed plans and regulations. The reality of the current situation is that it is unlikely that such a coordinated suite of plans and regulations can be created.

The impossibility of creating coordinated planning instruments has led to the increasing reliance on “Guidelines”, non-statutory planning studies that include public and other stakeholder consultation processes as part of their preparation. The “public” nature of the process to create these guidelines often builds up unrealistic expectations regarding their authority and efficacy on the part some participants. They often create misapprehensions on the part of the general public with respect to the degree to which they represent the future form of the city and neighbourhoods out of which the studies emerge. At best these guidelines represent the policies that some wish we had, but have been unable to secure through the conventional planning processes. At worst some of the more locally based guidelines are more like the results of an unscientific public opinion poll.

In “onbuildingdowntown” Baird et al suggested that,

“The object, after all, is not to replace one set of fixed arbitrary formulae with another set, but to enable the generation of innovative solutions to urban form that meet public as well as private needs. The object is also to have development controls that are capable of evolution so as to meet changing needs, and to tap the full resources of the development industry in that evolution.”(18)

The recent tall building guidelines and other planning studies have not proven to be accurate predictors of future built form or development intensity. The result has been a piecemeal and inconsistent approach to the approval of individual tall building projects. This in turn has generated a distrust of the official planning process in general – on the part of citizens/residents and proponents/developers.

Recent major debates (before the Ontario Municipal Board in particular) have focused on several key recommendations of the various tall building guidelines – those having to do with the minimum site dimensions required to support a tall building and the standards for sunlight penetration to existing public parks near to areas where tall buildings are anticipated or currently exist.

The reality in Toronto at this point in time is that, outside of the south part of the Downtown described above, there are very few consolidated sites or potential property assemblies remaining in downtown Toronto with sufficient dimensions to accommodate the minimum building setbacks and generic floor plate assumptions contained in the guidelines.

Yet, tall buildings continue to be proposed and approved (either by Toronto City Council or by the Ontario Municipal Board) on sites that are significantly smaller that the minimums established in the guidelines.(19) This is a phenomenon which is clearly going to continue, if the apparent precedent represented by numerous similar recent approvals is any indication.

Moving forward with development in the downtown, without a deliberate and workable theory of how tall buildings can be successfully accommodated on these remaining small sites will result in an extension of the “cognitive dissonance” that seems to characterize much of the well established and almost ritualized planning and development debates in Toronto.

Baird et al were prescient in their search for such a theory. They developed a broader description of the types of spaces of public activity and perception that could be found in tall buildings that would develop downtown.

Their “Five Levels of Public Activity” included consideration of conventional at grade open space opportunities as well as those that are below grade. (Toronto has a well-developed below grade weather protected pedestrian network called the PATH system.). They also discussed above grade opportunities including the potential for “less familiar” locations for publicly accessible open spaces at the “low roof” or podium levels and the high roof or penthouse open spaces.

Baird et al also warn against the reliance on the sort of generic standards that have emerged in the city-wide guidelines:

“The city consists of many different areas, but some guidelines are limited to a generality which may not apply to every different situation. What may be suitable for King and Bay may not be suitable for Yorkville and Hazelton. The guidelines may require adjustments to apply most effectively to a specific site.”

The most recent iterations of the City’s Tall Building Guidelines take performance standards that were developed for downtown buildings and extend them to the apply to all potential tall building sites on a city-wide basis, assuming that if it “works” in Downtown, it should work everywhere. Instead of the pursuit of creative approaches to new forms of space for public activity at all levels as suggested by Baird et al and for better ways to manage the interface between new building forms and the existing city, this extension is a form of “scope creep” that dilutes the design logic of the downtown tall buildings research in the first instance. This is not the sort of evolution that is discussed in “onbuildingdowntown”.

In the end what we can say about the City’s guideline documents is that: they apply where they can be applied. Where the underlying dimensional and typological assumptions cannot be applied, we have to be more creative. Unfortunately creativity is difficult to find in the public discussions and negotiations about the design of tall buildings. Proponents, citizens, architects and regulators all struggle with their different interpretations of the guidelines and with the assumption by some that they represent official predictions about the form of City. Despite their non-statutory status the guidelines have begun to operate as essentially “stealth versions” of more conventional planning instrument. This runs counter to the advice of Baird et al:

“Design guidelines cannot be accepted as a cure-all for the deficiencies of planning or zoning.”(20)

In the near future, it is clear that the City of Toronto will continue to grow by means of a fast-paced and tension-filled process similar to that which has been described above.

A key challenge for Toronto (its politicians, officials, the development community and the citizens at large) will be coming to the understanding that conventional approaches to planning are no longer particularly effective or useful as a means of understanding, planning for and regulating the dynamic growth of the City of Towers. In keeping with the ethos of the “open source” metropolis, the question of what system or approach can replace these existing tools and processes is open at this time and will be the subject of ongoing speculation and debate.

Mark Sterling, (with thanks to my editor and partner in crime Mary Jane Finlayson)

Toronto, November 2013.

[1] In this article, the term “downtown Toronto” refers to the area designated as the “Downtown and the Central Waterfront”, while “Toronto” refers to the larger amalgamated City and “Greater Toronto” and “the Greater Toronto Area” refers to the provincially designated area between Hamilton in the west and Clarington in the east. (see fig. 2)

[2] The Municipal Amendment Act, 1904 cited in OPPI Journal. November/December 2010 Vol. 25 No. 6 A Brief History of the Initial Zoning Power in Ontario and its Judicial Consideration: Leo Longo

[3] The City of Toronto By-Law No. 18642, the city's first comprehensive zoning by-law was enacted on June 10, 1952. Ibid.

[4] “onbuildingdowntown” Baird, McLaughlin, duToit, et al, City of Toronto 1974

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Pier Vittorio Aureli. The Possibility of an Absolute Architecture. Cambridge: MA. MIT Press, 2011.

[8] City of Toronto. Toronto Profile: Living in Downtowns and Centres, 2007 and 2012.

[9] Province of Ontario (June 2013). Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe, Office Consolidation, June 2013.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] The author is a frequent participant in hearings before the OMB, acting as an expert witness in architecture, urban design and land use planning for both public and private sector clients.

[14] Housing on Toronto’s Main Streets, an International Competition was organized by Lorne Cappe of the City’s Urban Design Group. The author participated in the competition and led a team that was awarded an honourable mention.

[15] Significant background documents include: “City Patterns, An Analysis of Toronto’s Structure and Form”, City of Toronto Urban Design Group; ‘The Open Spaces of Toronto: A Typological Classification.” Brown and Storey Architects.

[16] City of Toronto Official Plan Section 5.3.2 – Implementation Plans and Strategies for City Building

[17] “For what its Worth” Steven Stills, Buffalo Springfield 1966/67

[18] “onbuildingdowntown” Baird, McLaughlin, duToit, et al, City of Toronto 1974

[19] An example is the recent OMB approval of a 35 storey (107m) tall building proposal designed by the author’s firm on a downtown site whose site dimensions are 22.8m x 45.71m. OMB File No. pl060339.

[20] “onbuildingdowntown” Baird, McLaughlin, duToit, et al, City of Toronto 1974

Author Details

Mark Sterling is an architect, urban designer, land use planner and educator based in Toronto, Canada. Mark is the principal of Acronym Urban Design and Planning a Toronto based multidisciplinary design firm. Mark was a partner in Sweeny Sterling Finlayson &Co Architects Inc. (known as &Co) until January 2014. He is also He is an adjunct lecturer in the University of Toronto’s John H. Daniels Faculty of Architecture Landscape and Design and in the Department of Geography’s Program in Planning. He is also a frequent visiting critic and external thesis advisor at the University of Waterloo School of Architecture. Mark is the former Director of Architecture and Urban Design for the City of Toronto and is a member of the Design review panels for the Cities of Mississauga and Ottawa.

Glossary of Planning Terms (“Corresponding Italian Terms Where Available”):

Official Plan (Piano Regolatore Comunale)

An Official plan describes upper, lower or single–tier municipal council's policies on how land in the particular community should be used. It is prepared with input from members of the public and other stakeholders in the community. An Official Plan ensures that future planning and development will meet the specific needs of the community.

An Official Plan deals mainly with issues such as:

- where new housing, industry, offices and shops will be located;

- what services like roads, water mains, sewers, parks and schools will be needed;

- when, and in what order, parts of your community will grow;

- community improvement initiatives.

(Source: http://www.mah.gov.on.ca/Page1759.aspx)

Secondary Plan (Piano Particolareggiato)

Secondary Plans establish local development policies to guide growth and change in defined areas of the City. Secondary Plans are not prepared for stable areas of the City where major physical change is not expected or desired. Secondary Plans guide the creation of new neighbourhoods and employment districts while ensuring adequate public infrastructure and environmental protection. Secondary Plan policies adapt and implement the objectives, policies, land use designations and overall planning approach of the Official Plan to fit local contexts and are adopted as amendments to the Official Plan.

(Source: City of Toronto Official Plan Sec. 5.2.1 “Secondary Plans: Policies for Local Growth Opportunities”)

Zoning Bylaw (Regolamenti comunali)

The purpose and intent of a Zoning Bylaw in a municipality in the Province of Ontario is to regulate the use of land, the bulk, height, location, erection and use of buildings and structures, the provision of parking spaces, loading spaces and other associated matters.

Ontario Municipal Board (Tribunale d’appello di Pianificazzione)

The Ontario Municipal Board (OMB) hears applications and appeals in relation to a range of municipal planning, financial and land matters including official plans, zoning by-laws, subdivision plans, consents and minor variances, land compensation, development charges, electoral ward boundaries, municipal finance, aggregate resources and other issues assigned to the Board by numerous Ontario statutes.

(Source: https://www.omb.gov.on.ca/english/AbouttheOMB/AbouttheOMB.html)

Bibliography

Aureli, Pier Vittorio The Possibility of an Absolute Architecture. Cambridge: MA. MIT Press, 2011.

Baird, George; McLaughlin,

Stephen; duToit, Roger et al “onbuildingdowntown”, City of Toronto 1974.

Brown and Storey Architects ‘The Open Spaces of Toronto: A Typological Classification”, City of Toronto 1991.

City of Toronto By-Law No. 18642, (the city's first comprehensive zoning by-law) enacted on June 10, 1952. City of Toronto, 1952.

City of Toronto. Toronto Profile: Living in Downtowns and Centres, City of Toronto, 2007 and 2012.

City of Toronto Urban

Design Group “City Patterns, An Analysis of Toronto’s Structure and Form”, City of Toronto 1991.

Longo, Leo “Brief History of the Initial Zoning Power in Ontario and its Judicial Consideration, The Municipal Amendment Act, 1904” OPPI Journal. November/December 2010 Vol. 25 No. 6 A .

Province of Ontario Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe, Office Consolidation, June 2013.

Digital Sources

Province of Ontario Planning Policy (“Province” is equal to “Regione” in Italy)

The Planning Act (s.2 - Provincial Interest; s.16 - Official Plan)

http://www.e-laws.gov.on.ca/html/statutes/english/elaws_statutes_90p13_e.htm

City of Toronto Act (s.111 – Land Use Planning)

http://www.e-laws.gov.on.ca/html/statutes/english/elaws_statutes_06c11_e.htm

Places to Grow Act

http://www.e-laws.gov.on.ca/html/statutes/english/elaws_statutes_05p13_e.htm

Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe (s.1 - Introduction, s.2 –

Where and How to Grow and s.3 Infrastructure to Support Growth)

https://www.placestogrow.ca/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=9&Itemid=14

Municipal Planning Policies

Official Plan (Piano Regolatore) and Secondary Plans (Piano Particolareggiato)

City of Toronto Official Plan conformity to Growth Plan

http://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2009/pg/bgrd/backgroundfile-18337.pdf

City of Toronto Official Plan (Piano Regolatore)

http://www1.toronto.ca/wps/portal/contentonly?vgnextoid=fcb60621f3161410VgnVCM10000071d60f89RCRD

City of Toronto Official Plan Review (Piano Regolatore)

http://www1.toronto.ca/wps/portal/contentonly?vgnextoid=7ac5d58db2581410VgnVCM10000071d60f89RCRD

King-Spadina Secondary Plan (Piano Particolareggiato)

http://www1.toronto.ca/static_files/CityPlanning/PDF/16_king_spadina_june2006.pdf

Central Waterfront Secondary Plan (Piano Particolareggiato)

http://tinyurl.com/pj464fj

Design Guidelines

Bloor Yorkville

http://www1.toronto.ca/staticfiles/city_of_toronto/city_planning/urban_design/files/pdf/blooryorkville_final.pdf

Lower Yonge/East Bayfront

http://www1.toronto.ca/staticfiles/city_of_toronto/city_planning/urban_design/files/pdf/44_1yongestreet.pdf

Tall and Mid Rise Buildings

http://www1.toronto.ca/wps/portal/contentonly?vgnextoid=b20752cc66061410VgnVCM10000071d60f89RCRD

http://www1.toronto.ca/wps/portal/contentonly?vgnextoid=80a70621f3161410VgnVCM10000071d60f89RCRD

http://www1.toronto.ca/wps/portal/contentonly?vgnextoid=7238036318061410VgnVCM10000071d60f89RCRD

Other Urban Design and Planning Mechanisms

Design Review Panels

http://www1.toronto.ca/wps/portal/contentonly?vgnextoid=869652cc66061410VgnVCM10000071d60f89RCRD

http://www.waterfrontoronto.ca/our_waterfront_vision/design_excellence/design_review_panel

http://www.mississauga.ca/portal/residents/urbandesignadvisorypanel

Public Ream and Streetscape Standards

http://www1.toronto.ca/wps/portal/contentonly?vgnextoid=0e88036318061410VgnVCM10000071d60f89RCRD

Strategic Initiatives

http://www1.toronto.ca/wps/portal/....

http://www1.toronto.ca/wps/portal/contentonly?vgnextoid=0f8e86664ea71410VgnVCM10000071d60f89RCRD

Precinct Plans

http://www.waterfrontoronto.ca/east_bayfront/planning_the_community

http://www.waterfrontoronto.ca/explore_projects2/central_waterfront/lower_yonge_precinct_planning

http://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/2006/agendas/committees/plt/plt060601/it005.pdf

Master Plans

http://www1.toronto.ca/wps/portal/....

Zoning By-laws

http://www1.toronto.ca/wps/portal/contentonly?vgnextoid=2a8a036318061410VgnVCM10000071d60f89RCRD

http://www1.toronto.ca/wps/portal/contentonly?vgnextoid=....

The Ontario Municipal Board

http://www.omb.gov.on.ca/english/home.html

http://www.thestar.com/news/queenspark/2013/08/27/how_the_omb_stifles_democracy_in_ontario_cohn.html

http://www.thestar.com/news/city_hall/2012/02/07/....l

http://www.torontolife.com/tag/ontario-municipal-board/

http://abolishomb.ca/what-is-the-omb/

Site Plan Approval and Green Standards

http://www.waterfrontoronto.ca/our_waterfront_vision/our_future_is_green

http://www1.toronto.ca/wps/portal/contentonly?vgnextoid=f85552cc66061410VgnVCM10000071d60f89RCRD

http://www1.toronto.ca/wps/portal/contentonly?vgnextoid=3a7a036318061410VgnVCM10000071d60f89RCRD

http://www.toronto.ca/developing-toronto/pdf/guide_sectionD.pdf