BRASILE. Dall'architettura sostenibile, una nuova dignità urbana a cura di Carlo Pozzi con Claudia Di Girolamo

torna suBrazil 2013: project, landscape, ecology. Carlo Pozzi

Inhabiting landscape: Niemeyer’s works

Over the “short” century hangs Le Corbusier’s shadow, know-all architect, who apparently does not leave space to other characters who had a leading role, as histories of architecture show, even the most tendentious ones (Giedion lines up Wright, Gropius, Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, Aalto).

In order to show himself as a parallel figure, to be a giant in Latin America, with surprising European and world excursions, Oscar Niemeyer who starts as Corbu’s admirer from Brazil, with whom he cooperates for the project of Ministry of Education in Rio de Janeiro, we can only find a juxtaposition which might appear ideological but will remain formal risking formalism.

Does Le Corbusier suggest right-angle poetics? Niemeyer marries curve, of woman body and of the soft hills of his extraordinary Brazilian city.

The house of Canoas, where Oscar’s family lived from 1953 to 1965 – the year when they leave Brazil because of military dictatorship -, is inserted in a flourishing natural context in Barra de Tijuca, one of the outlying areas of Rio de Janeiro, a few minutes’ drive from the city centre: this architecture makes the site an element of the project, softly joining the height difference and making a treasure of it shown in the pictures that most celebrate its characters of sinuosity and organic harmony with natural elements, underline by the sensual sculptures realized by Alfredo Ceschiatti, a friend of the Brazilian architect.

As in the house of Frey at Palm Springs within the residence there is a rock, intentionally tolerated and highlighted in order to underline what we would today define the “sustainability” of the intervention.

Nature and architecture tend to belong to one another, to hybridize.

“I was worried to plan this residence in full freedom, adapting it to height difference without changing it, making it curve, in order to allow penetration of vegetation, without the separation caused by the straight line.”

This process is not different from what LC used for the manifesto-house in Poissy, near Paris, Ville Savoie used by LC as a scientific demonstration obtained by architecture by means of his five points (pilotis, roof garden, free plan, free façade, strip window); it also synthesizes the relationship between architecture and nature, which is mainly due to the privileged views that “new” architecture offers of the natural environment where is setting, first of all through the invention of the “fenêtre en longuer” that allows the maximus – in 1931! – rotation of glance towards landscape.

Another interesting comparison between LC and Niemeyer, N’s challenge to the most global architect of early ‘900, is between the two planned capitals: Chandigarh (1957) of Indian Punjab and Brasilia (1960), in the largest South American state.

The thistle-decuman structure of the two levels softens in its relationship with the existing natural context: LC inherits it from A. Mayer, regularizing its tree leaf design, Niemeyer inserts his architecture in L, Costa’s plan, the winner of the competition.

The comparison – more than between the residential settlements – is interesting between the Capitol with Himalaya on the background and the Square of Three Powers in the tropical savannah of “cerrado”.

The buildings of the Indian monumental complex are concentrated in an area which tends to be more and more separated from residential areas because of security reasons; LC has placed them on the ground after tracing the directions of the cardinal points: the south-north axis diagonally crosses the Assembly Palace. Places and orientations of the other buildings framing the site are based on this foundation element more than on references to the great examples of the past, from Moghul temples to the Prohibited City: the Secretariat, large east-west dam, and the High Court, same orientation but more open to the east winds.

In Brasilia, the two large trays of Parliament are settled, in opposition with one another, on a base, at a higher level than the large square that has Planalto Palace and the Federal Tribunal as side wings: between the basement and the square there is a large water basin, almost a memory of colonized nature. Parliament and binary towers are the focus of the monumental perspective which has communications tower at the centre, the extraordinary cathedral on a side, the sequence of the blades of Ministries.

Lina Bo Bardi and the ethnographic landscape

An architect arriving in Brazil in the second half of ‘900, immediately discovers the wealth of the production of material objects, the tradition of crafts that for centuries has taken charge of common daily necessities, often becoming real popular art.

Lina Bo Bardi who gets there in 1946 after the Domus experience and the cooperation with Gio’ Ponti has sensitive antennas and no intellectual Eurocentric pomposity: her research is fundamental for after war Brazilian architecture, with works such as Casa de Vidrio, MASP, the renovation (with new added volumes) of Pompeia factory and with strong participation to the debate on “tropical continuation” of the experience of Modern Movement. Of great importance is also her research on the link between artisan-artistic-popular-design link of new objects.

Lina contributes to the development of Brazilian culture starting from the study of her roots without ever thinking of putting them “under a glass” but trying to interpret them again for contemporary life, conceiving ordinary and artistic objects based on tradition.

Her drawings go from jewels to clothes, from dishes to chairs to stage design.

She is charmed by the simple beauty and clarity of Brazilian stones, especially aquamarine, malachite, blue topaz, rose quartz, that she has set in necklaces that are between tribalism and modernity: she understand this is a way for Brazilian jewels that ethically represent a contrast between semiprecious stones and expensive gold and diamond jewels. The project provides the added value.

The method used for clothes and set design is similar. She is uncomfortable with contemporary fashion, she prefers to draw for a “bad taste ball” (1949) and after to work with Glauber Rocha the other film-makers of emerging Cinema Novo, drawing scenes and posters (1960) with artist of research theatre for “Three penny Opera” (1960) for which she draws the poster, the theatre tools, the scenes, with intellectuals such as Camus for the costumes of “Caligola” (1961), with Teatro Oficina for “In the wood of cities” (1969) drawing the poster, the scenes, the costumes. Finally she represented “Pholias physicas, pataphisicas e musicaes” of Ubu of Jarry (1985) with an image between the dreamlike and hallucinatory: an ambiguous pig with two heads, made of cloth, which is now in her “Casa de Vidrio”, a dodecahedron sculpture, the platypus costumes.

Her creativity grows through the acquaintance of European and Brazilian artist and intellectual and through the extraordinary material Northeastern culture: she often travels in the dry Sertão areas, the so-called triangulo de la seca, in order to find objects of local craft. Lina is convinced that ancient manual and traditional manufacture combined with technological innovation and contemporary aesthetics, may increase the extraordinary original creativity of those communities and favour the growth of Brazilian design. Therefore she projects CETA – Centro de Trabalho e Estudo Artesanal, a workshop where native artisans and university designers can compare their experiences and test forms, lines, colours and materials. CETA would become also the site of her collection of objects from Sertão, archives of local memories where to find new models. But the years of military dictatorship arrive and the project will not develop completely. Only few years ago the collection of popular art of Sertão, followed by her decades before, was found in a government store, where it had been forgotten.

Her work progressively develops starting from the heredity of modern design contaminating it with Brazilian ethnographic discoveries; the burst of popular art has more and more space and two planning occasions allow her to experiment: the exhibitions in Pompeia factory that she had just restructured and the direct involvement in Bahia exhibitions.

In 1948 she was already working on the “first modern chair in Brazil”, folding, in leather and plywood cut straight (unlike the folded one by Alvar Aalto): from the steamers in Amazzonia she takes the traditional use of the hammock, applying a canvas which perfectly adheres to the body, to the three feet chair, in iron or wood, a sort of Tripolina linked to different traditions.

She goes back to modern design which looks for “pure” shape with Bardi’s Bowl (1951) in leather or cloth and iron structure. She then takes part in furniture competitions for Cantù (1957) with an idea of industrialization of artisan production based on the observation of how the caboclos of inland areas spend hours according crouched down at street edges without getting tired: to this elementary position corresponds a low bench whose angled leg, cut in a pattern from plywood, becomes the repeated support for furniture, chairs, beds, tables, hat holders.

But that popular way of stopping by a street edge is crystallized ten years later in a drawing which sets the distance between design and tradition: three branches and a log linked with a rope, as native people or scouts still to nowadays, form that street edge chair on which Lina has portrayed herself as the main protagonist of the experiment.

She deals in advance also with the theme of recycling, making of an old bulb a small paraffin lamp called Fifò.

The reinterpretation of popular themes with a synthetic and naïve approach overwhelmingly enters the architecture project as suggested in the flower banisters placed at the small empty spaces at the junctions between the new Pompeia building and the footbridge leading to the play fields and swimming pools: more recent regulations have required the juxtaposition of awkward and ordinary grates to the poetic “Mancacaru flowers” made of iron.

The prefabricated concrete little table with the central hole for the umbrella, mass produced (1986) for Belvedere da Sè in Salvador, with a view on Bahia of All Saints, owes its shape to the reinterpretation of “caxixi”, popular ceramic from Bahia.

Bahia is her great love of her last years and for Benin house she projects the renovation of the building which will hold it, with interesting connections and detachments between original walls and new structures, she covers wraps pillars with straw patterns of traditional baskets, she hangs cloths from the ceiling, she draws the restaurant as a large oblong hut of raw earth and roofs of wood and straw holding one only table with a circular elliptical shape with forty seats: you’ll be able, to sit, around and inside oh “girafinha” chair, a “poor” chair suitable for a museum of wonderful objects poorly produced by craftsmen.

In parallel with her new interpretation of objects of tradition and Brazilian popular art she organizes exhibitions in a showy sequence of colours and drawings: the sequence of Northeast in Bahia (1963) which Lina calls Northeast Civilization and shows objects linked to common use, shown as in popular fairs, and the sequence she shows in her Pompeia.

Favelas with a view_The luminous sky above Florianòpolis

In a time when intercontinental tourism is still for few lucky people, Le Corbusier flies towards Latin America and has the privilege of an overview of one of the urban settlements mingled with one of the most extraordinary places in the world: Rio de Janeiro Bay.

His recognition glance is already a project and the main idea is an infrastructure building linked to the ground and the hills where the Brazilian city lies. Advancing like a Roman aqueduct it shapes the structure of a new foundation of the city with the expressed aim to solve the problem of landscape and numbers of the informal settlements that crawl on the natural protections of the city.

A modern attitude that privileges the town transformation, risking to change the picturesque character so useful in international tourist agencies. We watch a first comparison/clash between the shapes of architecture – old and new at the same time – and the informal character due to the sum of barracks, in cardboard, wood, bricks badly built in a sequence one upon the other climbing the slope of one of the morros, the hills where a different Rio de Janeiro lives, sheltered behind favelas.

Nowadays we see phenomena which could not be foreseen at that time or few years ago, when favelas were controlled by drug trade and were often crossed by state interest only with military force: in the South American metropolis specialized agencies organized guided tours of favelas, sometimes in order to stimulate the sense of exotic and extreme, on board of jeeps like in a safari.

There are proposals for different tastes and economic availabilities throughout the city: from Vidigal Guesthouse, a pension with a “breathtaking view”, in the favela overlooking Leblon and Ipanema beach, at a walking distance, to the first Favela Inn, that opened in Mangueira Chapeù favela, on the hills of Rio, made possible after peace in 2009: it has three bedrooms that can host six people and balconies with a view on the sea, furnished with recycled materials: they declare they are inspired by the area life style.

Eneida M. P. dos Santos, a young Brazilian girl with a degree in hotel management, has organized Favela Receptiva, a tourist association which takes care of Bed & Breakfast, by selecting buildings promoted by the inhabitants of favelas, in order to assure tourists comfort, hygiene and security. The owners of these activities regularly follow English courses in order to improve their communication with guests.

To help tourism develop in these areas, the city has launched Rio Top Tour, offering the inhabitants of favelas training as guides.

This political/economical challenge moves from the consideration that Rocinha, the largest favela in Brazil and the theatre of bloody fights between drug traffickers and police, has been visited by almost two thousand tourists a month during the last two years: visitors are mainly German, French and American. They are travelers who avoid conventional tourist destinations and are used to looking for remote places in the world.

The clear risk is that this peculiar form of tourism, which is a great economic opportunity for so marginal contexts, may be moved by a sort of voyeurism of poverty, originating a mean charity which is far away from the real social redemption of the crossed communities.

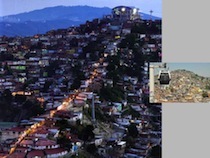

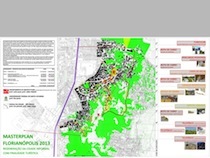

This is the reason why the theme of regeneration of Favelas in Florianòpolis has to be dealt with by means of a completely different approach. Florianòpolis is the capital of the state of Southern Brazil Santa Catarina, a little Rio with fascinating natural endowment. The first impression, arriving at the island linked with bridges to the mainland (state of S. C.), is to be under a more luminous sky than ours; maybe because of the lack of pollution and the frame of the sea contributes to reflect light, creating a territory mirror wrapping everything.

The second sensation is that of a city with a double image: from one point of view there is the tourist and playful character celebrated by its beaches (Canasvieiras, Ingleses, Daniela), by dunes and surfing schools, from the other the presence of favelas that have become historical, climbing up the slopes of Central Massif.

A double image that appears a contrast between naturalistic enjoyment and urban suffering of a social design that has characterized the Brazil we know and that nowadays is being faced thanks to the new economic possibilities of the nation or – to say better – to the attempt of a different distribution of wealth that has already created a middle class that did not exist twenty years ago.

A re-composition of the division between beauty and poverty is attempted in the inter-university workshop applied to the favelas system in Florianòpolis, towards a new urban quality that can make them attractive for tourists; they can be “captured” first of all by the privileged outlook on the landscape.

The modern theme of vigorous urban transformation has been left behind by contemporary procedures linked to interstice methods. Here it appears appropriate to work on a hypothesis of renovation both of the favela buildings the hills are studded with and of the streets and public spaces that have no identification yet. This is the occasion to provide informal settlements with urban dignity granting them a tourist appeal, inevitably linked to the security issue, constantly threatened by unorganized crime and narco-traffic.

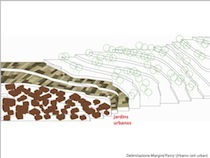

In Florìpa (as is affectedly called by tourist agencies) projects of social housing for an elegant urban acquisition are not necessary; what is important is to work an infrastructural equipment, on natural nets, to bring them to light and enhance them as an instrument for development perspectives in a tourist key. Informal settlements are often in the landscape, hiding it: regeneration projects must reveal it in order to cure it, making of it the treasure of the city.

The suggested tourism will never become voyeurism if a constant checking of community participation is the test paper for the success of the project.

The project which starts in Italian and Brazilian projects, will be introduced to the involved community by means of artistic and handcraft installations, capable of making it easy to share, simulations with prototypes that can become a system: a canvas covering a public space, the bright color of a façade with the notes of a samba school imprinted, a self propelled urban garden made with wooden boxes.

As a matter of fact the edge between informal settlement and the wood – that crosses the island – it tries to penetrate, may be solved by means of a system of urban gardens that can define the transit between what is built and urban scale park. The quality of the park that momentarily sees some town hall interventions as breach routes, observation points on landscape, wooden main entrances and little houses for tourist information and reception, is entirely played on the ability to make you get out of the high-sounding rhythm of the island city and to offer a fascinating glance.