Trentino Alto Adige. Una regione sostenibile a cura di Pino Scaglione, Chiara Rizzi, Stefania Staniscia con Edoardo Zanchini

torna suBrenner Motorway, A22 Autostrada del Brennero SpA: eco-boulevard toward osmotic infrastructure. Stefania Staniscia

The paradox of the chicken and the egg has struck again in architecture there are varying opinions on whether the spreading of settlements was caused by infrastructure spreading over the territory or the infrastructure network only followed the tendency of settlements to spread. Probably, apart from being totally meaningless, it is impossible to distinguish phenomena which are so intrinsically correlated. So let us use the idea of Bélanger, who wrote “infrastructure has grown in complexity vis-à-vis the current urbanization of the world. It is both a response to, and generator of, horizontal forms of development, in part due to the transnational distribution of technologies and techniques of urban engineering” (2012, p. 278).

At any rate, solving the problem is unnecessary if all we are seeking to do is finding new ways in which to think and implement infrastructure. In fact it is enough that we take note of how mobility infrastructure has conditioned, on different scales, the development or maginalisation of territories, the degree of their impact on the surrounding landscape, environment and community – on this, opinions are rather more unanimous – and in the ways they have the power to configure the spaces they cross, to understand that it is no longer possible to entrust infrastructure projects exclusively to specialist engineers that base their projects on standardised, mono-functional, stable and durable principles (Bélanger 2012).

This raises the question of whether the project should be omnicomprehensive and not just from the sector, if it must consider increasingly complex questions that need contributions from multiple disciplines. Ignoring the context into which an object/road project will be placed risks making object produced totally self-referential. Furthermore, it must be able to bring together the various disciplinary approaches into an overall vision in which no single element dominates but rather that an idea of infrastructure and common territory are shared.

A design condition that becomes still more complex when the current infrastructure system in the territory must be added into the equation. An infrastructure project is less and less a new project and more and more a project on what exists. “On the other hand, the economic crisis and the increased awareness of environmental quality over urbanized territory have made the saturation of new landscapes and the unsustainability of the logic of programmes to develop the physical infrastructure networks incrementally evident” (Ricci 2012, p. 192).

So we need a renewed approach to infrastructure projects, one that assumes a less specialised and more holistic attitude. But can one really consider this an invention if, already in the 1930s in the United States a team of landscapers, engineers and naturalists set up an interdisciplinary committee within the Transportation Research Board to tackle infrastructure projects in an integrated way (Gauthier, Pujol 2009)? This is the type of question this paper will try to answer.

A22 Autostrada del Brennero SpA commissioned a theoretic multi-disciplinary research work and experimentation project from the University of Trento to be carried out by a team led by Professor Giuseppe Scaglione. (1) –.

The research was set up as a continuation of the policy of the A22, which, aware of the close relationship between infrastructure, territory and community, has set itself some fundamental objectives, such as protecting the environment, sustainable development and technological innovation to increase safety and help the environment and sustainability. However, the company’s commitment is almost exclusively oriented toward tackling the eco-environmental aspects and resolving tout court its relations with the territory.

In fact they have made many investments in this direction, some examples: solar panels to serve as anti-noise barriers in the centre of Isera (1,067 metres), the setting up of innovative systems for the collection, treatment and disposal of rain runoff, implementation of led illumination systems to save energy, by putting in place an anti-noise plan that will result in long stretches being equipped with anti-noise barriers, the use of special sound-absorbent drain-asphalt to reduce acoustic pollution, the setting up of a centre to produce and distribute hydrogen at Bolzano Sud and experimenting with a hot recycling when repaving.

This is undoubtedly a virtuous approach, but it is only partial. It flattens the concepts of territory and landscape into that of the environment. The drawing up of a protocol between A22 and the University of Trento was a signal of change. The research work took on the complexity in all its dimensions, landscape understood as a synthesis of meanings that includes the concepts of environment and territory.

The A22’s need to find answers to three important questions was the reason why the study was commissioned. The first concerned the need to expand the motorway to solve problems of traffic congestion; the second concerned the project to make service buildings for the infrastructure less and less obtrusive and more and more compatible with the surrounding territory; finally the third concerned the requests advanced by the local communities that infrastructure impact be minimised above all in areas where this crossed inhabited centres – proposals of bypasses, tunnels, etc.

The research work, needing to translate these operative-practical needs into terms of theoretic-design reflections, consists in an overall rethinking of the function of infrastructure’s role, in particular in its relationship with the sensitive landscape context it crosses, which is Alpine.

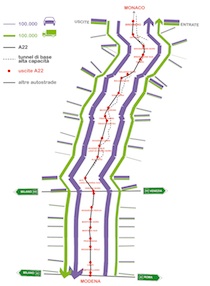

The point of departure of the considerations of the research group was an understanding of the current role of the Brenner motorway, not only in the local context, but also in the wider dynamics that involve the territories of the so-called Alpine platform. It forms an important stretch of Corridor I (Berlin-Rome-Palermo) and constitutes one of the main access points into Italy from the countries of central Europe both for commercial merchandise and for passengers (fig. 1). At the same time it serves a metropolitan role for local users who wish to move fast – commuters and/or users of “metropoli dolce” (Bonomi 2009) who move around to carry out the daily activities, for work or pleasure – and in some particular times of the year – the summer and winter tourist seasons – it fills with vacationers and weekenders that congest the motorway network (fig. 2 and 3). The presence of these two flows and the congestion that they produce is exactly what had induced the managers of this infrastructure to suggest a third lane as the possible solution to the problem and the works were planned to start on the first stretch, Modena-Verona Nord in the spring of 2011.

Faced with a problem defined in these terms, the first alternative hypotheses were made and they inverted the point of view according to which an increase in the volume of traffic must be answered by an adaptation of the road infrastructure in the direction of an increasing of its surface, using the logic that more traffic requires more surface. In substance, they moved from imagining the motorway in its “hydraulic” concept as an artery of large and rapid circulation to a new use of the motorway which goes beyond this to introduce the idea of infrastructure which allows one to experience the territory and the landscape in new ways that complement the styles of life produced by the new settlement conditions and have become occasions for a rethinking of the contexts it crosses. The motorway is no longer thought of as a tube through which it is possible to move from one point to another as quickly as possible and as efficiently as possible, thus, exclusively according to efficiency and safety parametres, but rather it is conceived as an object that relates and an opportunity to build new landscapes.

The infrastructure is interpreted as an “osmotic membrane that favours exchanges, compensations and new systems of relations with the surrounding landscape” (Ricci 202, p. 193) (fig. 4).

Osmosis in chemistry describes a solute moving between two liquids through a separating membrane. Figuratively it is used to refer to “reciprocal influence among several people, groups or elements that they exert on each other, above all when the ideas, behaviours or experiences of each party influence those of the others” (Treccani). The general common significance of the two meanings is that of a mutual exchange, of passage – from one side to the other of the membrane, either physical or ideal.

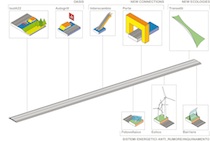

So by extension, when one uses the term osmotic infrastructure it refers to a “sensitive” mechanism – no longer “indifferent to the surrounding geography” (Lanzani, Pucci 2009) – but able to trigger an exchange mechanism between the context and the infrastructure that passes through the invention of “service” devices that serve as exchange and relation elements (fig. 5) in a linear system highly integrated with the context and from which it has allowed itself to become informed – in the literal sense of the word: endow with form – and that, in its turn informs (fig. 6).

So we have to imagine new words and a new syntax for osmotic infrastructure, rethink both the structures and the modalities by means of which the exchange will take place. We can or should reinvent anti-noise barriers, service areas, rest stops, exit ramps, flyovers and underpasses and all the necessary, but unoccupied/unused areas, buffer strips and residual areas outside the painted lane markers. Doors, islands and transects become the sensitive membrane: devices that function as generators of energy, impact minimisers – for the landscape and the environment -, traffic dissipaters, basins of calm, windows on the landscape and a brand to promote the territory.

Thus osmotic infrastructure becomes a component of the landscape, a tool to help one to get to know it, a machine to look and observe, to structure and reorganize the territory and an opportunity to enter a relationship with the landscape.

Bibliography

Bélanger, Pierre. “Landscape Infrastructure: Urbanism Beyond Engineering.” In Infrastructure Sustainability and Design, edited by Pollalis, Spiro, Georgoulias, Andreas, Ramos, Stephen, Schodek, Daniel. Oxford-New York: Routledge, 2012.

Bonomi, Aldo. “La piattaforma alpina nell’ipermodernità.” In La sfida dei territori nella green economy, edited by Borghi, Enrico. Bologna: Il Mulino, 2009.

Gauhtier, Daniel, Jean-Pierre, Pujol. Introduzione a Il paesaggio attraversato, edited by Lorenzo Vallerini. Florence: Edifir, 2009.

Lanzani, Arturo, Pucci, Paola. “Infrastrutture e territorio: le ragioni di un incontro ancora difficile,” Urbanistica 139 (2009): 40-46.

Ricci, Mosè. “Verso infrastrutture osmotiche.” In L’architettura del mondo. Infrastrutture, mobilità, nuovi paesaggi, edited by Ferlenga, Alberto, Biraghi, Marco, Albrecht, Benno. Bologna: Editrice Compositori, 2012.

Treccani.it L’enciclopedia italiana, accessed 15 October 2012. http://www.treccani.it/vocabolario/osmosi/

(1) This research was carried out by the DICA Department, today DICAM. It was commissioned by A22 Autostrada del Brennero SpA. The project was of Prof. Giuseppe Scaglione, University of Trento, coordinated by Prof. Mosè Ricci, University of Genova, Prof. Marco Tubino, Dean of the Engineering Faculty of the University of Trento, working group: Vincenzo Cribari, Chiara Rizzi, Stefania Stanisica; contributors: Thomas Demetz, University of Trento, Andreas Flora, Innsbruck University, Joerg Schroeder, TUM Munich; collaborators: Alessandro Busana, Valentina Ramus, Mattia Tamanini.