Apprendere dalla storia

torna suEnvisioning the Planetary

José Alfredo Ramírez

As part of the AA Earth Day event, I presented some ideas we are developing at AA Landscape Urbanism and AA Groundlab1. These ideas aim to envision the planetary as a way to reflect and contribute the rethinking and redefinition of our human-planet relations in light of the current crisis we are living through.

Envisioning the planetary is a project of representation that aims to become operational2. We hope, it will help us understand how planetary relations came to be (historically and geographically) and how they continue to work today, especially when the majority of them depend on landscapes and territories (with marginalised humans and non-humans at stake) that are hidden and invisible to our naked eyes but closely interwoven to allow and resemble the world as it is today.

To do this, we rely on knowledge and ideas we borrow to learn from alternatives to current models of urbanisation, (including those available from non-western perspectives) and strategies on how to unlearn methodologies entrenched in colonial and imperial practices3. As problematic as it might be, envisioning the planetary is entangled with the history of cartography and its genealogy of representing the earth, as a totalising entity, and therefore one needs to acknowledge that:

- Envisioning the planetary comes with agency as Denis Cosgrove wrote:

“Disk or sphere, modelled, pictured, or mathematically projected, the globe is known through its representations. And representations have agency in shaping understanding and further action in the world itself”4.

- Envisioning the planetary comes with risks:

Planetary representations have co-evolved with historical imperial and colonial traditions that have shaped contemporary mentalities and usually represent globalism hopelessly bound to exercising and legitimating authority over subordinate social and natural world5.

- Envisioning the planetary requires the clarification of what planetary might be in relation to other similar/complementary terms:

Earth, World and Globe described different aspects of our planet and are used to reflect specific interests, mentalities and processes so they should not be exchanged freely as synonyms. Following Cosgrove, these are some of the particulars for each:

Earth: is organic; the word denotes rootedness, nurture, and dwelling for living things. It also implies attachment and habitation: earth is the ground from which life springs, is lived, and returns at death.

World: has more of a social and spatial meaning. The world implies cognition and agency. Consciousness alone can constitute the world: humans go “into the world,” they may become “worldly”; they create life-worlds or worlds of ideas, worlds of meaning. World is a semiotic creation […]

Globe: associates the planet with the abstract form of spherical geometry, emphasizing volume and surface over material constitution or territorial organization. Unlike the earth and the world, the globe is distanciated as a concept and image rather than directly touched or experienced. As a globe, the planet is geometrically constructed, its contingency reduced to a surface pattern of lines and shapes6.

The planetary relations these terms foreground have been typically represented as total objects (such as satellite views) that can be managed or programmed and thus they simplify and reduce the diversity that earth and world, as concepts, might entail. But perhaps the planetary, as described by Jennifer Gabrys7 (following Spyvak and Wynter) can help open the possibilities for a different type of cartographic practices better suited to describe the range of relations across the plurality of humans, more than humans and the technologies and politics they are and could be embedded within. In her words:

The planetary is discussed as a figure of massiveness. Its invocation suggests total dominion: the rolling out of behemoth systems that hold the planet and all of its entities in a space of complete capture...Yet these images also lead one to ask: In what ways does the planetary become evident—whether as object, process, or event? How is the planetary configured, rather than assumed and given?... How might it be possible not to remake the pretensions of globality and globalization through planetary media projects, but rather begin to unsettle figures of totality and regulation in order to attend to the incommensurate, the unjust, and the yet to be recognized? 8

In this sense and despite its problematics, thinking and developing new and potential ways for cartographic and media to envision the planetary becomes urgent and necessary to project alternatives away to the climate breakdown or the pandemic of planetary impact we are experiencing.

To illustrate these ideas, I present a distinction awarded project from AA Landscape Urbanism developed by Elena Luciano Suastegui, Rafael Caldera and, Yasmina Yehia titled Just Transition in the Rhondda Valleys in Wales9. The project is as an example of what envisioning the planetary can entail by using a range of cartographic forms and imagery to depict how a given community in Wales, affected by historical energy transitions, are resisting and projecting alternatives forms of being planetary.

Just Transition, Treherbert, Wales

Through a partnership with the New Economics Foundation, the AA Landscape Urbanism programme was given the topic of Just Transition as part of an ongoing research to investigate energetic transitions from fossil fuels to green energy and the impacts they have in the wellbeing of communities in UK10.

The project is based in the Valleys of South Wales, where draining Coal in the past gave rise to an extractive system, that for decades fuelled Britain. Today the valleys have been abandoned, leaving behind deprived landscapes and communities with no opportunity to achieve a just transition.

Our students explored the story of these valleys framed within three different scales: A ‘Green’ transition under going on a global scale, ‘Green’ policies being applied in a regional scale and an existing ‘Green’ forest in a local one, and how these multiscale decision making process impact the way landscapes are being configured and how they can be represented.

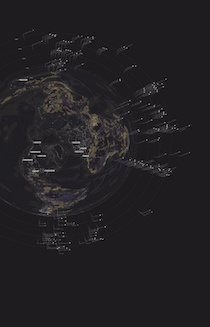

The valleys are the result of the different energetic transitions UK has seen historically. From coal extraction, that saw these valleys as the centre of production during the industrial revolution up the First World War, the abandonment and deprivation they suffered, when fossil fuel extraction moved to the North Sea and beyond for oil and gas, to today’s appearance of windmills and other renewable landscapes subordinated to transnational capital ventures ( image 01).

Image 01

As a commitment to the Paris agreement Westminster launched The Climate Change Act which aims at decarbonizing the nation by 2050 mainly fed by renewables such as wind and biofuels. The problem with this commitment is that only portrays an ideal green future for the UK because all actions in the Act are frame only within national borders obviating the huge impact of the UK fossils industry globally.

To explain this, Rafael, Elena and Yasmine produced a global atlas, a planetary projection used to show the concentration of green energy and just transition projects in the global north (coloured in white) and the gradual expansion outwards to the global south of the fossil fuel industry ( coloured in golden). They represent recent concessions explored by companies headquartered in London exposing a migration of the UK fossils apparatus towards the global south and suggesting a decarbonization achieved upon the instrumentalization of dirty energy extraction in the global south. A new green version of colonialism, this time waving the flag of climate emergency to justify its operations (image 02)

Image 02

What is observed on a global level is replicated in the Rhondda Valleys where coal miners, contributing to the expansion of the British empire overseas, were victims of centralized decisions. After WWI, the coal mines were shut, and people were given no choice to transition to a different sector. Since then, the Rhondda valleys underwent large depopulation and deprivation rates that are still the norm.

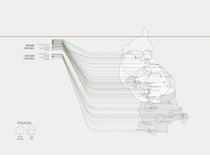

All the above was achieved through the implementation of policies. Rafael, Elena and Yasmine set out to produce a set of drawings that depict how policies have shaped the valleys. In gold are policies that refer to retail, housing and employment allocations that are more concentrated in the southern area. In green, the environmental actions are overwhelmingly dominant, particularly in the northern area (image 03).

Image 03

This dominance of ‘green’ policies in the north suggests an invitation from the local government to local people to migrate from the heads of the valleys to Cardiff, hinting at how authorities are hiding behind a green narrative to decamp the valleys and allow renewable companies to appropriate land.

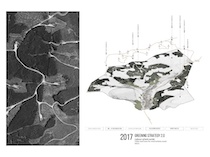

Treherbert, a local deprived town within the valley has been hit by these policies and as a consequence, two types of landscapes have flourished: a dense forest and bare land side by side. They are the result of a string of land policies implemented over the 20th century and have been depicted by students as follow:

After collieries were shot down at the beginning of 20th century, the forestry commission was created to acquire land and plant trees around the town. In 1919 the acquisition of land expanded to produce a forest for timber production to support the war efforts' in the future. This Land was consolidated with the expansion, in 1985, of new forest areas that were protected with a legal zone established in 1994 to ensure the enclosure of the forest and banning access and use to the local communities. By 2017 a new green strategy was established, and land was clear to allow the construction of windmills from a transnational company to extract energy from the valley(Image 04).

In short, historically the valley has been shaped by these policies and produced a vast forest and bare land that are next to but separated from the local community with no access or benefit from it.

Image 04

Existing forest resembles a factory rather than woodlands. Trees are separated 3 meters apart, stopping light to go through and effectively producing a monoculture land with zero biodiversity and impoverished soil with dead dirt.

Despite these conditions a local small organization called Welcome to Our Woods have been fighting for years for the opportunity to managed 4 hectares of forest to open alternatives for a different community/forest/planetary relation. Welcome to Our Woods managed to beat a labyrinthic sets of bureaucratic procedures to obtain the right to manage the land and convert the wood factory, that is the existing forest, into a live and biodiverse forest. The community is active by thinning the trees, using wood materials for biofuels, organizing community activities within the forest and building micro dams from existing streams, among others small interventions.

Rafael, Elena and Yasmina learnt from this experience and thought to expand it to the whole landscape of Treherbert, to the Rhonda valleys in Wales, and even serve as an example for a different type of policies that could potentially reconfigure UK landscapes through the lens of a local community at the heart of historically energetic transitions ( image 05).

Image 05

In this sense their project can be understood as planetary, as it aims to transform this valley from a dead forest and wind energy production for transnationals enterprises into a forest managed by the a local community with the capacity to create a community life dependent on its surrounding landscapes. Thus, envisioning the planetary entails learning from Welcome to Our Woods existing practices, the production of cartographic media to communicate the range of existing local skills and small landscape interventions, and the visualization and design of a set of policies that can make the project transferable to other parts of UK with a potential planetary impact.

Using as starting point the dominant landscapes, an overstocked coniferous land, and barren grassland, the project sets out to reach a managed status where a rich, diverse and healthy forest can be established over time benefitting Treherbert community through a set of designed interventions (image 06).

Image 06

These interventions start by applying community thinning, which is monetarily less preferred than ongoing mercantilist and productive regime called Clear-felling. Clear-felling produces macro- patches that are visually defined and cut at once with heavy machinery and with biodiversity and human access irrelevant for this model. In comparison, access to forest is crucial in community thinning for harvesting, monitoring and recreation, but it is also a main factor for soil and biodiversity disturbance. To minimize this impact, students propose the reorganization of the path system, using an algorithm to find the shortest path from all the points to a single gathering point, bringing not only logs, but also people together. They aim to combine this proposal with less heavy machinery and traditional methods developed by the community (image 07).

Image 07

So, how can the community do the job? Students also produced a handbook with 2 two parts: An inventory of the tools required, and a description to future generations, of the interventions needed to develop and improve the conditions imposed on the landscapes so the success of the plan in the future is guaranteed.

To envision a forest that is the result of both, community interventions and natural growth rates, students developed a digital model to simulate woodland dynamics. The model is based on growth, reproduction and tree mortality and it helps document in time actions and decisions taken. The digital model includes human interventions to exemplify how the removal of trees and building the path system will interact with the growth of the forest (image 08).

Image 08

The model is run several times to form what is called a ‘Shifting Plan’ which was applied in detail in a 200 hectares site besides Treherbert and is structure in three phases lasting 40 years. The shifting plan includes a full woodland coverage starting from areas close to the community in the lower part of the valley, to then moving towards the historically neglected areas at risk in the middle until they reach the upper part.

To achieve this, the project proposed the transformation of existing policies into a ‘Common Landscape Policy’. This policy supports economically, through a variety of subsidies and grants and technically, via the community handbook, the implementation of the overall strategy and local interventions such as: maintenance of stablished woodlands, the afforestation of barren land and of Riparian landscape, a new system of paths, community infrastructure (community hub and sawmill), sediment traps and woodland terracing and tourism infrastructure, all developed over a span of 40 years ( image 09).

Image 09

Finally, students designed a long section as a cartographic manifesto where they document the co-dependency their project aims to create, between the local community and the ecologies of the woodland as an exemplary landscape that put forward new human-planetary relations.

The section documents how existing barren land and overstocked pines requires more intense and long-term intervention and determination by the community. It also depicts a landscape that offers an alternative to connect the marginalised humans of the Rhonda Valleys and the diminished non-humans. In this sense this section is a way to envision the planetary, not by depicting a totalising object that can be managed and programme but by bringing to the fore those humans, non-humans, technologies and politics that are usually hidden behind planetary scale images ( image 10 &11).

Image 10

Note

1 Architectural Association Earth Day https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yun3XBDgBE4&t=187s accessed on 12th June 2020.

2 Harun Farocki, “Phantom Images,” Public 29 (2004): 12–22.

3 Potential history: unlearning imperialism / Ariella Aisha Azoulay. London: Verso, 2019.

4 Denis Cosgrove, Apollo’s eye: A cartographic Genealogy of the Earth in the Western imagination, 2003

5 ibid

6 ibid

7 Jennifer Gabrys, Becoming Planetary, E-Flux

8 ibid

9 Architectural Association Landscape Urbanism Post Graduate Programme, Just Transition Design Thesis: https://issuu.com/aalandscapeurbanism/docs/190920_aa_landscape_urbanism_just_transition_desig accessed 12th June 2020

10 The British Government is Fuelling Climate Disaster by Christiane Heisse Elena Luciano Yasmina Yehia: https://tribunemag.co.uk/2019/12/the-british-government-is-fuelling-climate-disaster accesed 12th June 2020