Re:

Reduce_reuse_recycle1. Mosè Ricci |

It all began in Detroit. Or, better, it began all over again in Detroit a few years ago, at the end of the last century. With the economic crisis that it had generated, the most important assembly-line city had to ask itself about its own survival and fate. In just a few years its population fell from 1,850,000 to 740,000. 2,000 buildings were demolished. For several miles around the center, the desolation is dramatically obvious2. Detroit is the Pompeii of American manufacturing capitalism, with more than 320,000 jobs lost between 2001 and 20083. Since the 1970s 57% of the population has left the city, 25% just in the last decade. Charles Waldheim, currently chair of landscaping at Harvard, Georgia Daskalakis and Jason Young understood immediately that something decisive for the future of the city and urban planning was happening at Detroit, and in 20014 began documenting it directly.

Ten years on, Detroit is slowly finding another dimension. Today the best itinerary to visit the city is called Cloudspotting Detroit, Best Places for Viewing the Sky and is promoted by local government. Despite its name, this tour leads the tourist (best if on a bicycle) to the most interesting places to visit, those which make Detroit worth visiting. There are not many. Only 31 places of interest for America’s 11th city, an ex(?)metropolis of 900,000 inhabitants in the urban area (there were two million in the 1950s). The important thing is that many of the first 16 conspicuous places of the city are, as Alan Berger would call them, drossscapes and others are evanescent. Demolished areas, abandoned parks, steam rising from manholes fed by underground heat, large abandoned public buildings, markets for used objects or where one can barter, Victorian villas reconquered by nature, houses occupied by squatters, re-naturalized infrastructure, abandoned neighborhoods that will be replaced by artistic installations… Clouds of dust, of steam or of tastes that substitute the traditional urban attractions (architecture, museums, libraries, Detroit even lacks some basic shops) and return the ruins of the assembly-line city to narration and nature, transforming Detroit into the first post-metropolis.

These ‘clouds’ are the icons of new urban devices, material or impalpable, that, in other terms, reduce, reuse and recycle what remains of the city in its landscape. Literally of course Cloudspotting does mean looking for clouds, things without substance and which often mean the arrival of bad weather, but they can also take on intriguing shapes, make one’s fantasy run and, suddenly, reveal the sky.

The modern city is finished in Detroit; its empty physical spaces no longer express an urban figure. This is something which is difficult to imagine from a European perspective. We cannot manage even really conceive it if we don’t see it first hand. The metropolitan area of Detroit is among the largest in the US. It could contain cities like New York, Boston and Philadelphia. In the center, within the famous eight-mile drive the elegant Victorian city built last century no longer exists as such. There are empty houses with walled up windows, others occupied by squatters, tall buildings with birds flying through windows, demolished industrial lots, abandoned shops, empty monuments, … have transformed this city in something else. In something that is much closer to an idea of a park and that, in the end, is not even displeasing. Beyond that eight mile circle, around this forming urban figure, the suburbs are surviving just fine. That is where the economic activity and the residences have moved. In the outskirts ( a definition which might be obsolete somewhere else) the highways are full of traffic and the malls are busy. Suburbia is doing well in Detroit, but the modern city died with the collapse of the economy that it had created.

There neither is nor ever has been an overall strategic plan to regenerate the center of Detroit. What is happening – the transformation of a wrecked city into a place which is moderately attractive, has increased real estate values (for the first time in the autumn of 2011 and by a higher percentage than elsewhere in America), the presence of the University as a stronghold and the taking of tourists through the restored Victorian villas, the repositioning of the Stadiums in the center of the city, the casino in the Greek area of the city, … - is occurring without design as disarticulated patchwork. But, something important is happening. It is not a requalification or urban regeneration. There is no appreciable attempt to regenerate the city or landscape of Detroit of last century. There is no current idea to restore the lost urbanity. Rather we find the creation of new value through the reduction of traditional functions, the reuse of derelict spaces and the recycling of surviving urban material. In the end, that is what it is, a process to recycle the urban figure generating new value through the attribution of a new sense to what there is.

The reading of the Alex McLean aerial images: the maps and diagrams which Stoss Landscape Urbanism used to elaborate proposals to activate recycling processes on an urban scale; Dan Pitera’s experiments reusing burnt houses and unused spaces5, the reduction of Michigan Theater to a parking lot, Arens’s “visions” centered on recovery practices constitute the epic of a city that is experimenting with the possibility of recycling itself, of another future for the city and for the discipline of the urban design project.

In this sense Detroit is a paradigm. It almost seems that the city’s current efforts are being used to better understand what Jane Jacobs meant in The Death and Life of Great American Cities beyond the banal “small is beautiful”. It seems that in Detroit the capacity to generate sense and beauty expressed by the idea of recycling after abandoning represents a new frontier for an ecologic project for the city and its landscape.

Recycling means putting back in circulation, reusing waste materials that have lost value and/or significance. As a practice it allows one to reduce waste, limit the presence of refuse, lower the costs of disposal and contain those of production of new. In other words, recycling means creating new value and new sense. Another cycle is another life. The propulsive content of recycling resides in an ecologic action that pushes what exists into the future, transforming waste into prominent figures.

Architecture and the city have always recycled themselves. Examples like Split, like the Theater of Marcello in Rome or the Cathedral of Siracusa, just to cite three of the most obvious examples, are manifests of recycling. These are not restorations. The idea of preservation tends to embalm the image of architectonic or urban space attributing value to the immutable. In recycling, change is the value, when it manages to generate figures as those in the cases we cited.

The innovative aspect of the contemporary condition resides in considering this policy strategic for the city, its architecture and derelict landscapes. The recycling paradigm is in contrast with the paradigms of new construction and demolition that have dominated the period of modernity, but not banally. What interests us here is only observing the recycling experiences that produce culture, beauty and urban quality for the city.

The practice of recycling spaces and the urban fabric is necessarily contextual and adaptive. One cannot put in place stereotyped techniques or traditional instruments. Every place and every case requires a different project. One can speak of several tactics, in the sense in which Fabrizia Ippolito uses this term to refer to urban actions6 that correspond to a single strategy of intervention, a strategy aimed at increasing the quality of the city’s environment and landscape while, on the other hand, eroding the density of the metropolitan functions.

The idea of recycle implies a history and a new existence. It involves narration rather than measure. Its field of reference is landscape, not territory. The idea of territory asks from architecture: quality, stability, persistence over time and projects as authorial decisions to establish competitiveness among locations by means of the author’s signature. The idea of landscape instead does ask architecture for defined times, it asks to be able to age together, to change continuously as the landscapes change and it asks that the project be stratified, decided by many, accepted by many, and contribute to the construction of that landscape-portrait, a beautiful image by João Nunes, the portrait of a society and not of an author.

In this sense the strategy of recycling represents the conceptual background and general objective of a series of projects that mark a crucial phase of contemporary urban design culture. It is the passage from a system of measures (the territory) and the system of values (the landscape). Perhaps the most interesting experiences are those that involve the entire city and identify a collective, non-sporadic undertaking, which demonstrates the possibility, consensus and convenience of a different type of urban development.

In 2008 in Munich, the Administration together with the presentation of a variant in the general urban plan decided to announce a competition for young designers, under 40. With Open Scale, this was the name of the competition, Munich asked young architects to imagine Munich in the years 2020-2030. The same future they will live and design. The project Agropolis by a group of designers coordinated by Jörg Schröder7 won. It proposed that agricultural areas producing food in the city occupy temporarily empty spaces as they awaited new construction. This episodic logic shortening the supply chain could be expanded ad used on a regional scale occupying increasingly larger spaces and redesigning the metropolitan landscape. Moreover, the cultivation of gardens can, like an epidemic, expand till they contaminate terraces and roofs of private houses and public parks which are too expensive to maintain. This is a social policy, that concerns food quality and the quality of the citizens’ lives and that takes into consideration rural nature, the aging population and the employment crisis. But it is also a landscape strategy to redefine the image and the overall urban quality by redesigning and imposing a governance on the city’s open spaces, which are again productive. It the recycle project of an obsolete urban structure in an agricultural landscape which can express new aesthetic and environmental qualities of the city. Or, as Pierre Donadieu said, Agropolis is “a bearable Utopia of agri-urban landscapes”. Munich opened the first construction site for Agropolis in 2010.

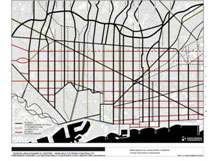

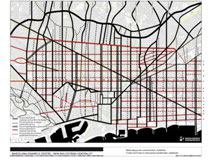

Also Barcelona is recycling itself. In the city packed with synergetic action, contemporaneity and not completely integrated, the architectural studio Gausa-Raveau with its Multiramblas project, the Office of the Assessor for Urban Ecology directed by Salvador Rueda with a plan to vastly reduce the urban impact and the geographer Francesc Muñoz’s seminar on Recycling Barcelona are elaborating a multifaceted strategy to recycle the block-fabric of the Plan Cerdà. The concept of intervention is linked to the adopton of a scheme analogous to that of the GATPAC-Le Corbusier plan that manages traffic flows in 3X3 block units rather than a 1X1 unit. Within this supersquare driveways are to be recycled into public spaces, green areas and urban gardens. The Office of the Assessor of Urban Ecology gave its okay to the first interventions of re-naturalization of the first driveways in 2010. On the other side of the city, on the hills beyond the airport, another project is on its way toward completion. This is the re-naturalization of Barcelona’s largest urban waste dump (150 hectares situated in Garraf Natural Park), which was already full in 2006, after having accepted more than 20 million tons of waste dumped there in a valley for a depth that reached up to 18 meters in some points. The project “la vall d’en Joan” won the prize for the energy category at the World Architecture Festival 2008. The idea of the project, which cost 11 million Euros, is to clean up the site collecting the energy produced and cover it with a carpet of plants set on 11 terraces to be used for agriculture and where several species of native plants are cultivated that require low amounts of water and have a low environmental impact. The center for biogas in the area will produce about 550 million cubic meters of methane. The project produces a depolluting action and a phase by phase restoration of the environment. In about 15 years the recovery cycle of the environment will be done and the shape of the project still today easily recognizable will vanish into the surrounding landscape, like a Zen work, cancelled by the nature that returns everywhere.

In Brussels, Gilles Clement has realized a small, but extraordinary project as the manifesto of an expressive force. L’Escalier Jardin is an operation of de-monumentalization. It is like an insult to the traditional city, here a useless monumental structure is left to be invaded by spontaneous nature and recycled as a garden of biodiversity. In Paris, the Ile Seguin by Michel Desvigne is becoming a park among the ruins of a Renault factory.

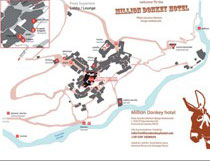

Not much is happening in Italy yet. Perhaps the State Railways are the main actor in the recycling of uraban structures. Among the several underway that of the Officine Grandi Riparazioni (Workshops for Big Repairs) by the Studio 5+1aa, is probably the one that best interprets the sense of time with an open and in part unfinished project that transforms this apparently incompleteness into added aesthetic value for the city. At Prata Sannita the old center of the village has been transformed into Million Donkey Hotel by Feld 72. This is a collective operation to recycle an abandoned village creating an embryonic hospitality structure to demonstrate the possibility of survival in urban conditions where population is falling which is typical of the interior areas of Italy’s center-south.

In the United States two cities, New York and Detroit, are roposing two different declinations of the paradigm recycle. In New York the High Line and the Fresh Kills landfill, both projects by James Corner Field Operation (with Diller, Scofidio and Renfro on the former) demonstrate how recycling projects can be attractive and glamorous and how contagious they are. Their capacity to generate emulation and imitation at their margins produces requalification effects and new economies. We wrote about Detroit at the beginning. After the crisis of the industrial economy the city disappears and the suburbs beyond the 8-mile divide continues to function. What we are unprepared for in Detroit is not only the disappearance of the figure of the modern city but even the absence of n idea of development.

1 These notes are a synthesis of the content of the urban planning and landscape sections of the exhibition Recycling Strategies for Cities and the Planet (MAXXI, Rome, November 2011-May 2012)

2 Edward Glaser, “Brains over Buildings”, in Scientific American special issue 305,3. New York, September 2011.

3 Data from U.S. Department of Labor, 2010

4 See Charles Waldheim, Georgia Daskalakis, Jason Young, Stalking Detroit, ACTAR, Barcelona, 2001.

5 Dan Pitera is Executive Director of Detroit Collaborative Design Center at the University of Detroit, Mercy School of Architecture. He lead the community engagement team made up of DCDC staffers, representatives from Community Legal Resources (CLR) and volunteer who serve as Process Leaders and Project Ambassadors

6 See F. Ippolito, Senza Paura, in Ventre. La rinascta dell’architettura n. 2, nuova serie, Cronopio, April 2004. Monographic issue on the city and fear

7 See Jörg Schröder, Kerstin Weingert + bauchplan, Agropolis München, Munich, Germany, 2009.

|

EWT/ EcoWebTown |