USA:

ReCycle Columbus, Kay Bea Jones |

|

THE CASE OF COLUMBUS

American baby boomers grew up believing that Christopher Columbus discovered America. The power of that myth is not lost on the capital city of the State of Ohio that is his namesake. Columbus, Ohio is not the oldest or most populous city in a state that has provided 8 American presidents; a state that fostered the agricultural and industrial development of 19th century America. Columbus can be counted among the Midwestern boom cities of Detroit, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Toledo and Indianapolis, now striving to emerge from an industrial past. But Columbus is unique among them with a most fluid identity open to perpetual reinvention. Not tied to specific capital industries or family dynasties, Columbus is a product test market, appreciated for its homogenous demographic cross-section. The city can claim no monumental landscape features or physical characteristics to qualify the incorporated city of a million and a half residents. Instead government, universities, banking and insurance are dominant sectors of its economy, and they continue to draw people in.

Unlike other Midwestern metropolises, Columbus is growing in population. While politics and scholarship exhibit fluid dynamics, financial institutions are relatively conservative and static, and they serve to anchor the historically moderate community. Service industries define the flat territory whose downtown skyscrapers are nodes for two intersecting interstate freeways. Service employment has provided relative economic stability during seasons of post-industrial collapse for older urban centers in the region. The current story of recycling, revising and rebuilding in Columbus begins with jobs, a prerequisite to architecture and urban design innovation. But myth and invention are the other side of the same coin.

Recycle, as illustrated in MAXXI’s exhibit, opened doors to a widely varied definition of what constitutes the regeneration of an existing element or environment. The MAXXI curators’ strategies for architecture were freshly disparate in scale, locale, and intention, while strategies for the cities in its collection were idealistic, and implications for the planet were speculative. Rossi’s faite urbaine, or urban artifacts, were best exemplified in innovations such as New York’s High Line , Portaluppi’s Wagristoratore and Tschuni’s Le Fresnoy in which the symbol of the original remains present even as its meaning is diverted, appropriated, or stolen. Buildings and landscapes alike that drew from the culture of the pre-existing condition offered more poetic results, and those realized trumped those merely proposed.

MYTH AND REMAKING COLUMBUS

It is useful to define the idea of recycling that can currently be observed in Columbus. With each centenary, the image of Columbus, the man, gets recycled. The monumental statue of the Genoese admiral located in front of city hall, a gift from the City of Genoa, circa 1950, was joined by a facsimile of his Santa Maria for local 1992 celebrations. At that time, two renowned buildings by Peter Eisenman arose Phoenix-like from the ashes of the past: the Wexner Center for the Arts (1989) and The Columbus Convention Center (1994). For the Wexner, Eisenman reconstructed fragments of the lost Armory, the former Ohio State University campus headquarters of ROTC (the training facility for reserve military officers). This manufacture of images presented a real history from artificial massing to set his avant-garde structures against. By his next major building, any local history was passé as his formalist archaeology gave way to new metaphors, and the previously demolished railroad terminal designed by Chicago architect Daniel Burnham that had occupied the downtown site for almost a century was not cited in Eisenman’s massive convention hall. The candy colored volume of torqued and twisted empty volumes articulated a new formal language devoid of the past and its celebrated elevation was the one seen from flyovers above.

The City of Columbus’ post Post-modern phase now requires projects less formally idiosyncratic and more focused on addressing the real social and urban problems of housing, mobility, employment, and social and environmental sustainability through the use of complex integrated systems. The myth of the power of architecture familiar as the Bilbao effect has been demystified by harsh economic realities resulting the mortgage foreclosure crisis and weak political will.

Columbus potential for recycling is a rebirth. Work currently underway will revitalize nearly 100 acres of prime real estate located between the cities downtown central business district and The Ohio State University’s campus of 50,000 students and 4000 faculty. The key to this urban revitalization is the statewide funding program that provides resources to clean up existing brownfields making dirty and abandoned infrastructure once again useful for commercial and residential inhabitation.

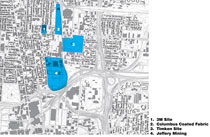

[Include Columbus map showing noted areas]

Local developers have successfully transformed a former margarine factory into the extension of the Harrison West neighborhood with 96 new single family homes packed in , new urbanist-style, along with a block of flats, a community center with pool and gym and a public park along the Olentangy River, one polluted by factory by-products. The project catalyst was the millions of state land clean-up dollars. The project has become the model for subsequent projects in process, each recipients of the same state investment, that include Columbus Coated Fabrics of 18 acres, Timkin Roller Bearing Company of 30 acres, Jeffery Mining and Manufacturing of similar area, and a funerary monument and casket company along the industrial railroad corridor that span north from downtown toward the university. Speculative proposals for these areas begin with new models of dense, affordable housing with bicycle corridors and transportation infrastructure that enhance options for mobility. The 3.5 acre former 3M metal coating factory is currently being developed as a new food center for entrepreneurial food based business and neighborhood distribution of local food products.

Recycling in Columbus is beginning with the erasure of so much massive infrastructure, much of which has been marked by creative urban arts. Most of these structures are being completely demolished, not only by developers’ heavy equipment, but also by arson as a manifestation of self-destructive forces from within the city. The detritus of years of graffiti are erased with it. The grand, flat landscapes that are being salvaged in this process will require a coherent language of occupation, presumably with stimulating new myths. The question remains whether those new stories will come from within their communities or be manufactured wholesale from imported narratives, and how its architecture will arise from the ashes to define a new paradigm.

|

EWT/ EcoWebTown |