Edvard Ravnikar: Revolution Square in Ljubljana - The poetic Illusion of the Metropolis

Ales Vodopivec (translation from Slovenian: Vesna Holzner)

Ales Vodopivec (translation from Slovenian: Vesna Holzner)

Ravnikar bitterly stated several times that Ljubljana did not have the character of a national capital, because it lacked classicist architecture and metropolitan stretches. In 1960, when he won the competition for the architectural and urban planning concept of the Revolution Square complex (today Republic Square), this is what he wrote in his article on the development of modern Ljubljana: "With a certain delay after the Western cities, Ljubljana was also touched by the fresh wind of urban planning reforms from the mid-19th century, best known for Haussmann's reforms and projects in Paris… As the paragon and the visual concept of the required city space, we should imagine a practical classicism adapted to general use..." For our most famous representative of modern architecture, such observations seemed strange and hard to understand at the time.(fig.1)

In that respect, we should bear in mind that, when Plečnik came back from Prague in 1921, Ljubljana was still a small provincial town of some 40,000 inhabitants. Plečnik introduced some crucial urban planning moves, landmarks and numerous interventions in public space, managing to change the provincial character of the city and to provide Ljubljana with recognizable metropolitan features. But the issue of a modern city center was still open. And Revolution Square was supposed to bring a representative splendor to the city.

Already in the 1950s, when he won the first prize in the urban planning competition for the design of the center of Ljubljana, Ravnikar prepared the first studies on how to change the former garden of the monastery of nuns into a central city space with crucial administrative and political buildings, seats of state institutions and government offices, a large square for mass events and a pantheon of deserving people.

When the competition for the Revolution Square complex was published in 1960, Ljubljana had more than 130,000 inhabitants, having truly become the capital of the Republic of Slovenia, complete with all the scientific, cultural and political instutions. The area of Revolution Square was supposed to symbolically define the space of the capital of the republic, with a monumental square and a monument to the revolution.(fig.2)

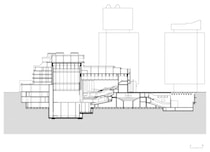

Plečnik had planned the city, Renaissance-style, as a "big house"; Ravnikar was also intensely involved in the contemporary issues of urban planning. His competition study for the new regulation plan of Ljubljana, chosen in 1940 as the basis for further city development, introduced the first elements of the more modern urban planning of Le Corbusier: dividing the city into zones – residential zone, industry zone, green zone, city center – and, most of all, stressing the importance of road and rail communications. However, his proposal for Revolution Square shows that he, like Plečnik, would not separate architecture from urban planning. Unlike most pioneers of modernism, who were interested in the autonomous object in space, Ravnikar always saw the spatial context as the source of the architectural concept. Building in an urban environment was a challenge to him: how to harmonize new, modern architecture with older built structures. He rejected self-sufficient or (as he used to say) "exhibitionist" architecture, because he believed in a dialog between the new and the old. Ravnikar's project for Revolution Square is distinguished by the thoughtful placement of three independent buildings, resolving the complicated situation of the wider space, which combined the historical complex of the former monastery and church of nuns with the residential buildings of the architect Vladimir Šubic, built before the Second World War. With two 20-storey three-sided skyscrapers, he created a symbolic portal where he set up the monument to the revolution. In this way, he marked the "Ljubljana Gate", a geographic name that became prominent in the past because of the particular situation of the city between two hills. He laid a long parallelopiped to shut off the monastery complex from the new representative square, lying along the axis of the assembly palace, designed by the architect Vinko Glanz. By doing this, he gave a spatial and visual border to the geometrically irregular structure of the monastery buildings, creating three smaller squares at once, with different characters and scales. Numerous passages between the buildings, displaced construction lines and multiple levels resulted in an unhindered flow of open space in all directions and the merging of new structures with the complex of the monastery and church, as well as other buildings in the immediate vicinity of Revolution Square. After the early, perfectly symmetrical plans, Ravnikar gradually turned to more dynamic spatial compositions.

After the suppression of more modern and liberal politics in certain republics in the early 1970s, the construction of Revolution Square as the symbol of Slovenian sovereignty was completely halted in the subsequent years. The abandoned construction site clearly showed that the political and economic situation had changed all over Yugoslavia. The construction could continue only when certain buildings were taken over by new investors. Political ambitions gave way to business and commercial plans of the main centers of financial power: Ljubljanska Banka, Iskra (the biggest Slovenian company of the time), and the Emona department store. This, of course, brought changes to the original urban and architectural plan. The monument to the revolution was moved to the western fringe of the complex. The dominant verticals were reduced to half of the planned height, but new peaks brought a certain dynamic quality to the symmetrical composition of the symbolic "gate". Next to its base, the requirements of the new investors introduced ground-level buildings, changing the geometric regularity and simplicity of the original concept.(fig.3)(fig.4)

The buildings on Revolution Square show that Ravnikar respected the fundamental features of modern architecture – in other words, volume instead of mass, regularity instead of symmetry, no decorations – but he did, in many ways, remain faithful to classical architecture and especially to Plečnik. Coming back from Vienna, Plečnik brought Semper's theory of skin or cloak, which is also visible in Wagner's opus, as the Germanic tectonic tradition; similarly, when Ravnikar was in Le Corbusier's studio in Paris, where he worked for some months before the Second World War broke out, he was introduced to the Anglo-French tradition, the architectural mindset of enlightenment, which gives priority to authentic building material and authority of construction. Ravnikar saw the accented, sculpted construction as a fundamental source of the architectural concept and thereby also architectural expression. He was always intrigued by the contemporary possibilities of construction and interested in the tectonic logic of the building in the sense of a structural approach. Still, he always provided buildings with a recognizable façade envelope.(fig.5)

Therefore, the concept of a skyscraper with a strong bearing core and jutting storeys, which was daring from the standpoint of construction, is hidden today behind a vertically accented façade cloak of granite slabs, which Ravnikar fastened – like Wagner in his postal savings banks in Vienna – with visible screws. A similar treatment of the stone façade envelope distinguishes other new buildings on the square, especially the lower, horizontally accentuated building of the Emona Maximarket department store. For later buildings, Ravnikar used other materials too, especially visible bricks, or the white stone covering Cankarjev Dom.

Ravnikar's buildings invariably have three parts: the ground floor reveals the construction of the building, the raised body is cloaked, and the roof – or rather a modern paraphrase of a roof – is usually the most freely formed element, clearly showing the specific rhythm of the whole. The final processing of applied materials, locally produced as a rule, is based on the industrialization of contemporary construction. The simple building details are innovative, just like the whole Slovenian architecture of the time. Innovation made up for local shortages, the technically backward and undeveloped modern building industry, and the low availability of foreign markets of new building materials and technologies.

Revolution Square was built over almost three decades; more precisely, from the first proposals of the mid-1950s to the completion of Cankarjev Dom in 1983. Again and again, Ravnikar tried to accommodate the programmatic and investment initiatives with "open design", which was a novelty for him too: "It has been years since the design 'down to the last screw' became inadequate to the objectives and complexity of today's needs. The road has changed; keeping in mind the new unforeseeable situations, the changeable constellation of partners and the fluctuations of financial and technical possibilities, we should not only keep control over the course of events, but also guarantee a better quality of realized desires." The greatest changes in the original project were needed after most of the square was already built; moreover, it was required to use the remaining space to build the Cultural and Congress Center, later called Cankarjev Dom (1977-83). It demanded extraordinary organizational, architectural and construction efforts; in fact, some of the numerous planned halls and auxiliary premises had to be built deep under the square, even under the finished buildings. As a result, Ravnikar managed to preserve the relations between the structures above ground, where he coupled the volume of the large hall with a longitudinally accented, impressive reception space including the main portal.

Most of the complex of the cultural and congress center, with a large concert hall, a medium hall for various stage performances, a round hall and auditorium for films, numerous rooms for conferences and meetings, as well as other auxiliary premises, was located on the second level below ground. In those times, the architect was completely subjected to political forums, which actually made decisions about the number of seats in each hall, in accordance with the planned number of delegates at party congresses. But Ravnikar still managed to design the room geometry so as to guarantee excellent sound and vision. In the decades that followed, the attendance at the artistic and cultural events, fairs and congresses in Cankarjev Dom surpassed all expectations, turning the place into the central Slovenian cultural institution.

The commercial street with small shops and entrances to specific contents of this area, from the department store and the garage to Cankarjev Dom, connecting the northern and southern edges of the complex in the form of a passage, is an element of Ravnikar's wider concept of a major city pedestrian artery, going through the city center alongside Slovenska Road, withdrawn from car traffic.

When presenting Revolution Square in 1973, Ravnikar wrote a long text showing his interest for social anthropology of space: "Our citizen, lacking experience with scale, sees this complex as a product of megalomania, while others consider it insignificant, but the truth can be discovered only through everyday use, when we can feel it as a space of meetings, a central space for national events, a location for necessary social programs that would be hard to host elsewhere."

In that sense, he lived and worked hoping that his creative efforts would not disappear in a void, which he expressed like this: "...if, despite the dominant technology, there is a momentary triumph of poetic illusion, it will completely satisfy what the architect seeks in his work". (fig.6)(fig.7)